FEATURES

FEATURES

Label Spotlight: Trackwork

Having just recently celebrated the label's 5th birthday at Australia's most prestigious venue, the Sydney Opera House, Trackwork has found itself at the centre of music's most exciting cultural crosspoints, Jonno Revanche writes.

A city as proud of its own beauty as Sydney cannot exist without many working hands making light work. For every example of “perfection” there is the slowcore reveal of its perfect opposite: a tradie in tattered high-vis, a gardener in oily workwear, an aesthetician in nitrile gloves, readying filler to pierce skin in some sterile white room. This is not the classical definition of the sublime. A great beauty exists, and then there is Victor Hugo’s idea: that something rare and specific occurs at the meeting place between that and the grotesque, countenancing (and by virtue of the strict comparison, illuminating) the former.

The Gadigal Land/Sydney-based label Trackwork, formed in late 2019, plays off this varied meaning. The producer UTILITY (Austin Benjamin) sources their name from a similar principle, sounding more like a demonym for an imagined city beyond anyone’s reach. UTILITY feels like it should be a verb, but it works like a noun.

It evokes the working class undercurrent of Sydney and its ever-present state of being “under construction”, seen through tools, scaffolds and rigs (however you interpret that), scattering the city, while also speaking to some multidisciplinary nature shared among the team of Austin Benjamin, Elia Bosshard, Isabelle Laxamana, and Mali Nakalevu.

“Obviously, people assume that it is working on the rail.” Austin Benjamin tells me, when I bring it up. “Whenever I would come to the studio - whether it be Sevy or Bayang - I would time box the day, and I would literally write ‘track work’ to refer to the making of production or creating with artists.” On their website, a quote from Vv Pete is somewhat more instructive.

“We call it Trackwork because we put in the work.”

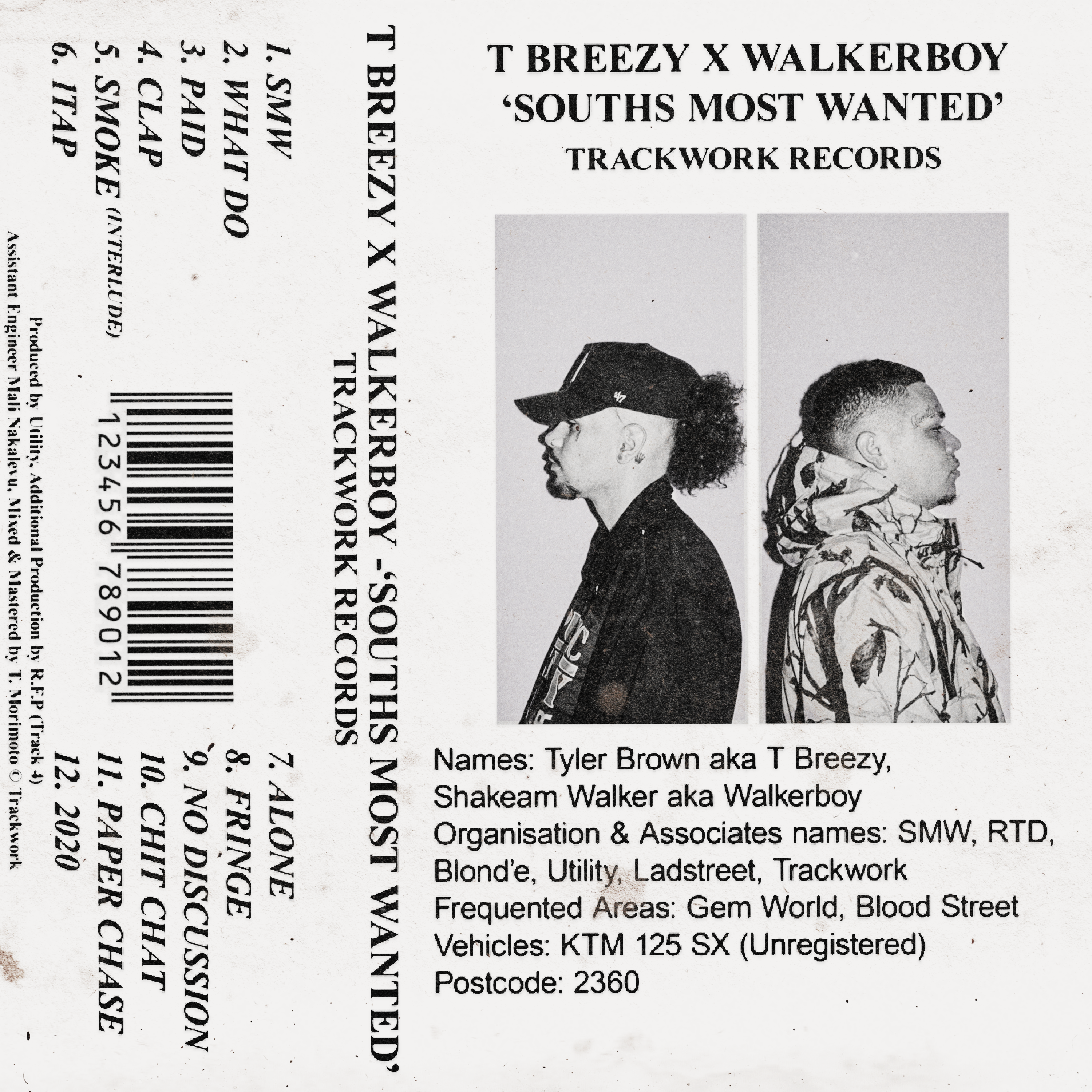

The genesis of its meaning has little effect on its interpretation. That is, their status as one of the most culturally important factions of artists currently operating in Australia, and possibly globally. Representing artists like Vv Pete, DoloRRes, and Gamiliraay rappers T.Breezy and Walkerboy, the label has succeeded in carving out a space to champion the work of the sui generis, artists with overlapping histories who approach the word “artist” practically, operating in the space between contemporaneity and “life.”

They draw from what is in front of them rather than abstraction, neither purely conceptual nor naively expressive. They may be autodidacts, mentored by family, educated traditionally, discovered by community, or stitching together a practice from nothing in prison, only to arrive, energetically, at the same place, in the very same moment; becoming artists whose work resists the very categories they inhabit. Trackwork represents their indeterminable nature. No label in the country is quite like it.

PHOTO: TRACKWORK OFFICE, CREDIT: JONNO REVANCHE

Dualities exist beyond the matter of name. Despite the recent explosion of new hip-hop artists in Australia, whatever adventurousness seen from the new wave comes through in a chancey switch between style, form, flow, and aesthetics rather than a necessary detour through genre. Ventures into club music, in particular, or crossovers between the two, have been constrained. Even by virtue of their backgrounds, the producers at Trackwork have incorporated these influences into an indelible producer's ethic, making the connection between the two more explicit.

I met the team behind Trackwork at their studio on Oxford Street, right in the heart of the “gaybourhood” - not technically a haven for hip-hop artists or their producers. Hip-hop is now considered party music, so the narrative goes. During Sydney’s prime, and particularly at the peak of the late 70s, the livelihood of Oxford Street depended on necessary alliances between the police, gay small businesses that propped up nightlife, and “small businesses” - ie, dealers, in order to facilitate the continued success and peace of each. What fascinates the casual observer of the area may not be easily attributable to these factors, which may not appear in “official histories” or in the steady language of zoning documents, but they nonetheless contribute to an aura. It somehow ushers people in, like a vacuum.

The idea of such a crossover, as in a crossing of a track, or a line bifurcated, extends to form. Austin’s background as a sound artist, as someone with at least a tangential relationship to installation, contemporary art, and “forward-thinking” work more broadly informs something as quotidian as the crafting of a beat. Building the muscle memory of making a sound and knowing how it might connect with listeners mid-air - that quality separates the nature of a good producer at a laptop from a serious one. “It's just those were very different areas, very distinct areas of my practice that were interlocking already before that.” Austin shares.

Elia Bosshard is more clear-sighted about why this might be the case. Describing herself as label manager and producer, artist manager, and general fixer-upper, ie, a Capricorn, her eye works like that of an editor across the many aspects of Trackwork’s output. The ability to understand editorial practice and publishing requires complex thinking that happens quickly, which is as close to a true definition of intelligence as any of us can get. She also happens to be Austin’s partner.

“Me and Austin have been together for a long time, and have both had long-running arts practices that have existed alongside each other.” She relays to me, from inside the red velvet-lined recording room of the label’s office, where words seem strangely truncated by the elimination of an echo. ”I used to run this magazine called ADSR, which was very multidisciplinary, and focused on anyone at any level, any career stage, any background could contribute - it was very democratic.”

“It was, in some sense, a way of creating one of those spaces that seemed to be in rebellion against what Sydney red tape doesn’t want us to do. I think I've been on both sides enough now, having worked in cultural institutions and the indie scene. There’s a huge divide.”

Therein lies the rub. Many of the artists working with Trackwork accurately ‘represent’ Sydney in its barest terms, in all its contradictions, but often aren’t actually ‘represented’ by Sydney institutions - whether they be museums, galleries, venues, publications, or other official providers. What goes on day to day, in exchanges between people, in the minds of its residents, feels like intense psychic material (Austin describes it as “psychotic and entrepreneurial”) which many fail to grasp, and translate. Personality lies downstream from production. The inference from institutions could be that the everyday matters that inform city living might be too strange, contradictory, or unusual to be translated in such a way. Or, that the avant-garde is not true of an artist living beyond the rim, touching the lip of those Sydney suburbs like Mt Druitt, where Vv Pete lives - despite birthing Onefour, Australia’s most sought-after drill group. That Vv Pete’s face has appeared in New York City’s Times Square but otherwise remained on the “outside” of Sydney spaces gives pause.

CREDIT: JADE D'AMICO

I bump into Vv Pete at the studio one day, and confronted with the energy of someone so self-possessed without saying a word, I suddenly understand, after 33 years of living, why people use words like “star.” Everyone in Sydney believes they are an undiscovered celebrity, but that is completely different to holding court with someone both classic and idiosyncratic, whose energy suggests something so evident of an above or a beyond. Which is to say, someone whose future success is obvious to you from one meeting.

“This is how I started: I wrote to ‘Super Bass’ by Nicki Minaj.” Vv relays to me, sitting opposite me in the office now, cooling herself with a tiny electronic fan. (I silently wonder whether queens are born or made.) “I started doing freestyles around year 7. I was always best friends with the dictionary. I’ve always been into reading and writing.”

I suggest that this image is somewhat reminiscent of stories about Mariah Carey bringing a thesaurus to the studio. Her eyes light up. “From then, I started going to street university at Mt Druitt around 16. I met mentors Esky and Stan Bravo. They had this thing at the time called Street University Live Sessions, where they would pick an artist once a month and stream them live.”

Back then, Austin was working at ACE Parramatta within some of the youth programs during COVID. “Previous producers were investing with me, but weren’t taking next steps - didn’t want to do videos, marketing, things like that. Me and UTILITY got in the stu (sic) and found out we worked really well together."

"Utility is always taking on my opinion when it comes to production or mixing. I’m actually able to have input on my ideas. It’s not a battle zone - I feel free.”

It is the artists they represent - Gamiliraay rappers T Breezy and Walkerboy, hip-hop artists Sevy and Bayang, and early intrepid recordings with artists like Serwah Attafuah (now a renowned digital artist) that challenged the Sydney hegemony and set the terms for what Trackwork could be. Releases like #3Badman By Snooe Badman and Nexus Destiny with T Morimoto (released on DJ Plead & Morimoto’s SUMAC label best known for spearheading Logic1000’s career on her self-titled debut), served as expeditions into the sound that feel definitive of Trackwork’s current incarnation. But it is within the collaboration with Vv Pete that this applies more clearly: an artist who said that early dealings with producers, labels, or institutions were helpful but couldn’t match the breadth and imagination of her ideas, which went far beyond the scope of simply a “local.” Working with the trackwork team saw these ideas beginning to match the vision and the cross-genre sound they were looking for.

CREDIT: DAYVIS HEYNE

That sound —the club music that shaped Trackwork —has a genesis. Four years after a market crash, young millennials believed - naively or realistically - that they were the first generation to create cutting-edge music entirely shaped by the internet, taking it back into a local mixing pool to make something interesting in real-time, among others who shared the same conviction. Much of the music I encountered during my initial, intrepid visits to Sydney and in the first few years afterwards fit this brief. Although Melbourne was the most skilled at modelling their sounds after cities like London, New York, Berlin and Hong Kong, Sydney remained the city most convincingly tethered to those places, envisioning a world replete with independent, forward-thinking music that saw a horizon beyond institutions like Triple J, variegated in genre despite being fit for the club. Or, unfit for ‘the club’, but perfect for this one.

“Everyone felt like something really interesting was happening at the same time, and, like, centred around, like, GoodGod small club, and different clubs like that,” Austin notes. “It was very much a physical meeting spot for artists, labels, and community.”

I would attempt to describe this club music (indeed, I am describing it) as the deconstructed kind, evocative of a sensibility that could’ve only existed then. Others have made some not insignificant attempt at assigning words to made-up sounding genres, all of which is ultimately irrelevant because the correct descriptor is vital. “It reminds me of when I first got to uni, and I was like, shit, everyone's better than me. I've got to practice.” Says Austin. “And then it drives you. There was a similar period I was listening to what, like, Marcus (Whale) was making, or like Lavurn (Cassius Select) was making. T Morimoto was hugely influential as an ongoing mentor. Very early on, I heard his music through Sia Ahmed (Founder of DIY Label HelloSquare and now Director of MusicACT). She was massively influential to the idea of starting my own label.”

Certain trends have emerged since then. Though Austin Benjamin says, prefacing this with the realisation that it could sound cliche to say out loud, that they merely look out for work that is good. Maybe to someone with their feet planted on that hallowed ground, it’s obvious. Still, something holds. One senses a unifying ethic in the artists who engage with Trackwork, a kind of energy which feels real enough, rather than a so-called brand. The casual observer might be able to discern a focus on club and hip-hop, but there is also something more complex—a sense of a DIY mode of working, without arbitrary aesthetics. A connection to the ongoingness of punk and metal, which escapes the trappings of both.

“Austin is very sensitive to artists who are creating work in that way.” Says Elia. “Just giving space to artists to be who they are, not trying to fit them into a box.”

A rich origin story suggests a glut of raw material that reaches far beyond the industry plants and featureless, frictionless artists chosen by record labels to be drawn into development deals and represented on pasted-up banners around the city. “To get support on a larger scale in this country, you have to tick boxes.” Elia shares. “And I understand like there's a whole process behind that, but maybe that's where we can be. A bridge to connect these two very disparate worlds. Because otherwise artists, like T breezy, Walkerboy, Vv, all these artists, they just get missed.”

There is a somewhat fixed, yet expansive, emphasis on the visual representation of artists in the stable. Vv Pete, in particular, thrives in the realm of the public.

“Ever since I started rapping, I could see the hunger in the crowd,” Vv says. “It’s the results I see, the results that my team consistently delivers. Anyone can be a star, but it demands that you ask, ‘How do I create my universe?’ How do you want to sit on your throne?’ What this studio provides for me is a risk-free answer.”

Trackwork is honed in on this thing, something local, a sensibility that contains the granular, the mixed, the clandestine, and the inexplicable. It is the elan vital of all these kinds of DIY oriented historically formed communities with histories that aren't just trends, nor just TikTok music, but long-standing connections to a community or history that birth creation. That specificity has its own ring. It grabs your attention. It’s what draws Austin to artists, and only makes sense that centring that would apply to others as well.

“I remember going to Southside Inverell with T Breezy. Meeting people’s families and getting to know people’s unique personalities is a really core part of it. People like Kelman Duran, a Dominican producer based in LA (who we brought out for Vivid in 2023), we’ve become friends with. He somehow got a Princess Loko / Tommy Wright the 3rd sample on a Reggaeton beat onto a Beyonce record (‘I’m That Girl’ Renaissance, 2022), which, alongside his incredible catalogue, is this insane cultural feat."

Sonically, their interests stretch beyond the predictable drama of genre. There is a reverence for negative space, and an ability to honour how minimalism isolates the sexier, more propulsive elements of a beat. “When I was studying, I was obsessed with Pierre Schaefer and the whole music concrete kind of approach - how you could loop a recording of a train and make it interesting,” Austin explains. “He totally spearheaded this mode of thought that then travelled into the BBC radiophonic workshop, and then into what is now sample-based music.”

In short, listeners are hungry for something beyond the ahistorical, of the minutiae of online culture that strips all context away from the lineage of one track, in the vein of a TikTok sample with its metadata excised. A typical Trackwork release resists that kind of amnesia. There is an emphasis on being able to reference or not reference, “for it to be somehow specific melodically,” and to use sampling in such a way that connects parallel histories. A hyper fixation on building each track around its relationship to percussion, “from my history playing drums” and polyrhythm, fortifies the approach. Becoming a producer wasn’t some preordained title but a result of strange, sidelong collaborations. A kind of backdoor path into the tradition: part consigliere, part director, rather than a mere beatmaker.

Credit: SNOEE BADMAN - #3BADMAN COVER ART, TRACKWORK

“T. Breezy came to the studio on one of our first sessions, and we were already producing left-field stuff. And he was just like, let's you know, keep making this.” Says Benjamin. “He kept coming back every day. Everyone was like, Who is this kid? He kept going, “Where are we going to release it?” I knew no major label in Sydney that would touch something like this. It was so no one wanted to really hear about it, other than Amelia at fbiradio.”

T. Breezy was one of the first collaborations that informed what Trackwork would become. Other highlights include the recently released Varvie World by Vv Pete, featuring collaborations with Brodinski, Formation Boyz, and Kelman Duran. Trackwork unites these avant-garde ideas; those that might work in institutions often don’t move outside of them, often convening in a way that is outside the white cube gallery, seeming like spaces made for educated people by educated people. All that grit, theory, and potential is streamlined into tightly contained spaces, with nowhere to go beyond the four walls. Trackwork is the opposite of that. “Vv has these amazing South Sudanese community days, just like in their local community halls,” Elia says. “Those events happen through all sorts of communities around Sydney, and unless you're connected to it in some way, you might miss them - but they're no less vital.”

The point is to reconnect those threads. “I think, like, the role of a producer really should be to create the framework for artists to make work in a way that is rigorous but also has the freedom to embrace the moment.”

“Spaces made for educated people by educated people” sounds like an all too literal description of somewhere like Sydney’s Martin Place, which on any given day hosts so many men in suits that you wonder why the makers of ‘The Matrix’ ever considered shooting their film anywhere else. It also hosts the CTA business club, one of those beautiful, absurd, brutalist buildings in Sydney that, at once, seems made for public appreciation and yet remains inaccessible. The Trackwork team had been going to CTA for years, and managed to be one of the few artists in recent years to have convinced the owners to play a show there.

“I actually fell into Trackwork when we did the club service show,” says Elia, “and it was the first show we did with Vivid when Kelman Duran came. I was in my element, bringing the show together behind the scenes, designing, setting up the space, and then Austin curating the program.”

There is another barrier. While it might seem unremarkable in another city, the partitioned nature of the Sydney city into eastern suburbs, inner city, inner west, western sydney, and the peripheral cultures and pockets that surround it have often encouraged an inflexibility toward cross-over, movement, or cultural interplay that is taken for granted here and comes off as tribalistic everywhere else.

Sydney being the first point for ‘Australia-as-colony’, the classism that seems so native to England, formed as it was (or as historians say) out of the feudal system, reinforces a loyalism to either old school aristocratic ties or convict style camaraderie that seems unshakeable and sometimes a deterrent to necessary cross-pollination, skill-sharing, or a trust in the unfamiliar.

Early maps of Sydney show this in a more literal sense, displaying areas deliberately designated for convicts, soldiers, and elites, meaning that the idea of a cultural feedback loop existing, hundreds of years later, seems more plausible. Austin acknowledges, also, the socioeconomic implications of those disparities that “are rarely acknowledged” in the cultural analysis of Sydney artists.

The impact of COVID, which occurred near the beginning of Trackwork in 2020, compelled many artists to think locally. There is something to be said about the positive repercussions of such an inwardness, one that Trackwork has achieved where others failed, while they were inside baking bread or creating experimental ceramics.

PHOTO: TRACKWORK 5TH BIRTHDAY, SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE, PHOTO: JORDANKMUNNS

It is now 2025. The label's fifth anniversary has coincided with a show at none other than The Sydney Opera House, as part of Vivid Live’s ‘Studio Parties’ series; arguably Australia’s most revered venue, at home and across the globe. The Opera House is an institution that embodies many of the contradictions inherent to Sydney itself - a building created under workers’ control, representing a feat of public imagination, only to act (most often) as a vessel for the country’s most exclusive. The city’s most prized venue reflects the impossible dreams of many Sydneysiders. For those in attendance, the show proved instead as a remarkable merging of worlds, not only for Trackwork’s appearance in the Opera House Studio, but as the first time baile funk would sing out through its halls.

To perform there as an artist, too, is to claim a legitimacy that is largely symbolic. For Trackwork and Vv, that legitimacy has been theirs far longer than Australia’s culturally inclined institutions have been willing to recognise it.

In this moment, and across much of what these collaborators have done, it’s obvious: Everyone else is still playing catch-up.

-

Jonno Revanche is a freelance writer based on Gadigal Land/Sydney, find them on Instagram.