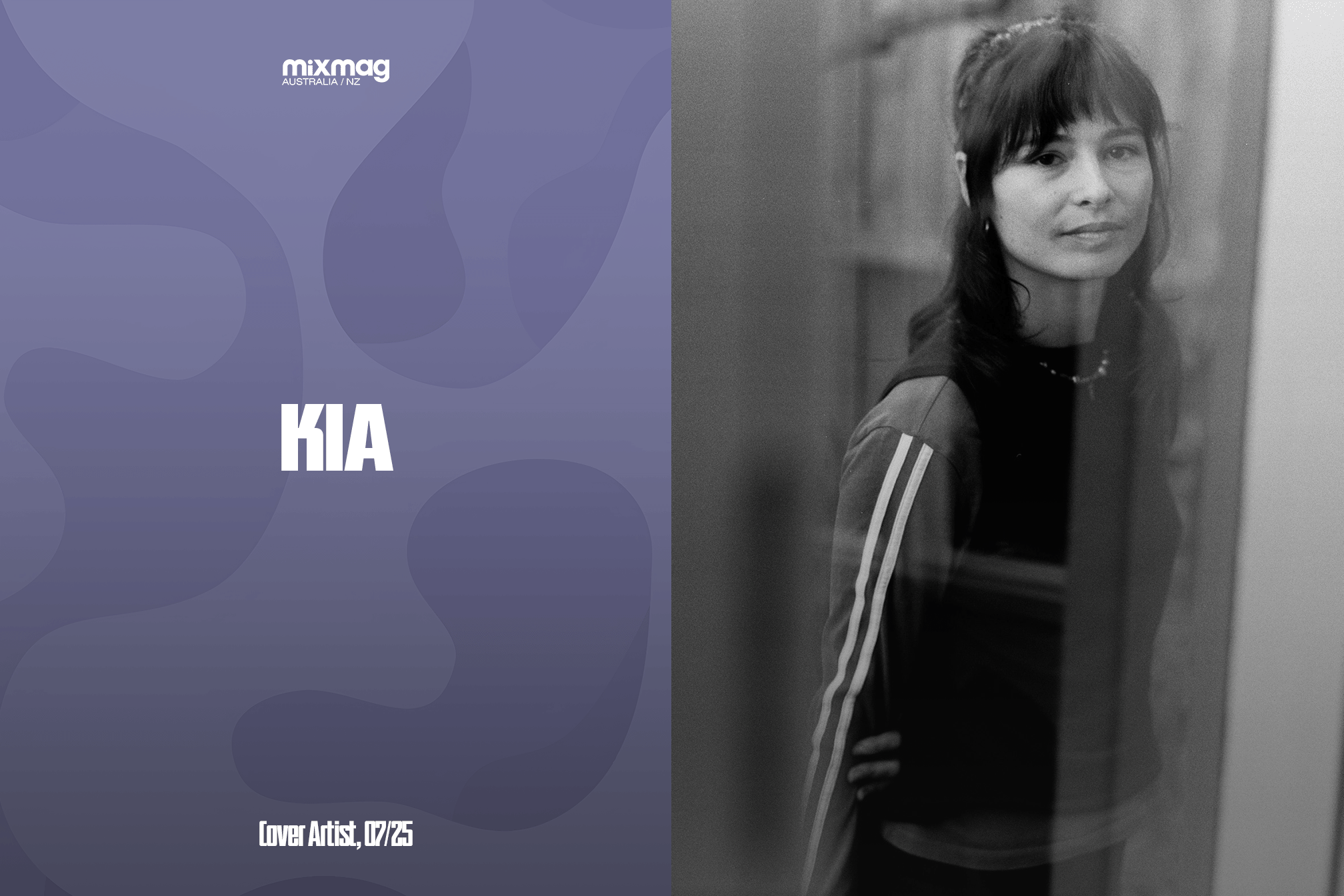

COVER STARS

COVER STARS

Kia: A shared sense of scenius

The Animalia & Cirrus label head, un:send festival founder & DJ is Mixmag ANZ’s Cover Artist for July 2025.

I first became familiar with Kia in the early days of 2020.

The collective consciousness of that time is one marred by distress, uncertainty and a general discomfort exacerbated by our inability to connect.

Her mix for c-, ‘wandi the flying dingo’, was named after a dingo of the same name who fell, presumably from the claws of an eagle, into the backyard of a north-east Victorian home. For this writer, and undoubtedly many other listeners, the mix provided a much-needed retooling of what electronic music meant at a time when it lacked as much of a social framework as it does today. While the mix was released in November 2019, this slow, moody, textured, and considered approach to track selection was, and still is, something that Kia pioneers across everything she does.

In an era where the DJ has merged with or superseded ‘the influencer’, we’ve become accustomed to the idea that being a successful DJ is an endeavour that can be achieved with the right grind. TikTok tutorials, the content machine, debates around gatekeeping, and the sheer number of self-proclaimed DJs in the space are symptoms of a culture which has, to many, become a goal. For some of the world’s most well-regarded DJs, their success may appear to many to be a result of a hustle-hard mentality.

Kia’s point of difference often puts her comfortably at odds with the glamour and hype that dance music has become associated with.

Kia, DJ, Animalia and Cirrus label head, as well as un:send festival founder, is Mixmag ANZ’s Cover Artist for July 2025.

Australia’s ‘sound’, an undeniably contested idea, has long been one steeped in an acknowledgement of the cultural and political landscape that gives rise to its sounds. Art has always stood as a reflection of culture, creativity and expression in the time it is made. For dance music, the ‘art’ that a person produces is even more beholden to contextual factors.

For Kia, one of Australia’s most talked-about DJs of the time, it's this context that informs everything she does. An acknowledgement of what came before her is so crucial to how she operates.

Born on Gadigal Land/Sydney but a Naarm/Melbourne local since she was 19. A move that has firmly placed Naarm as an addendum to her name, Kia has, for a number of years now, stood at the very centre of a new wave of Australian music, garnering huge support and influence not only here at home, but also overseas.

Kia’s roots in dance music began like those of many others, applauded by and in the safety of her friends. “I learned how to DJ at illegal parties my friends were throwing, and that gave me the freedom to experiment and test things out,” she reflected. “It really led into how my sound still is now. I wasn’t used to playing like, banger after banger.”

Having grown up in Sydney when the lockout laws were introduced, Kia is all too aware of the impermanence of spaces that house forward-thinking dance and electronic music. After moving to Melbourne, she credits Inner Varnika festival with helping to shape her openness to music of all kinds, particularly in live settings.

“I went religiously from the age of 18 until it finished two years ago,” she remembered. “The music was always really diverse, and I didn’t necessarily adore every single set that I saw, but I loved the experience of it. The sound system, the bizarre context, and every artist interpreting how they played into that space, was always a really cool lesson.”

Outside of her friendships with many DJs and producers now regularly referenced as some of Australia’s most visionary, she credits artists like Moopie with introducing the idea of what her place in Naarm’s musical tapestry could be. “His 2018 set (at Inner Varnika) was one of the most influential sets on me ever,” she shared.

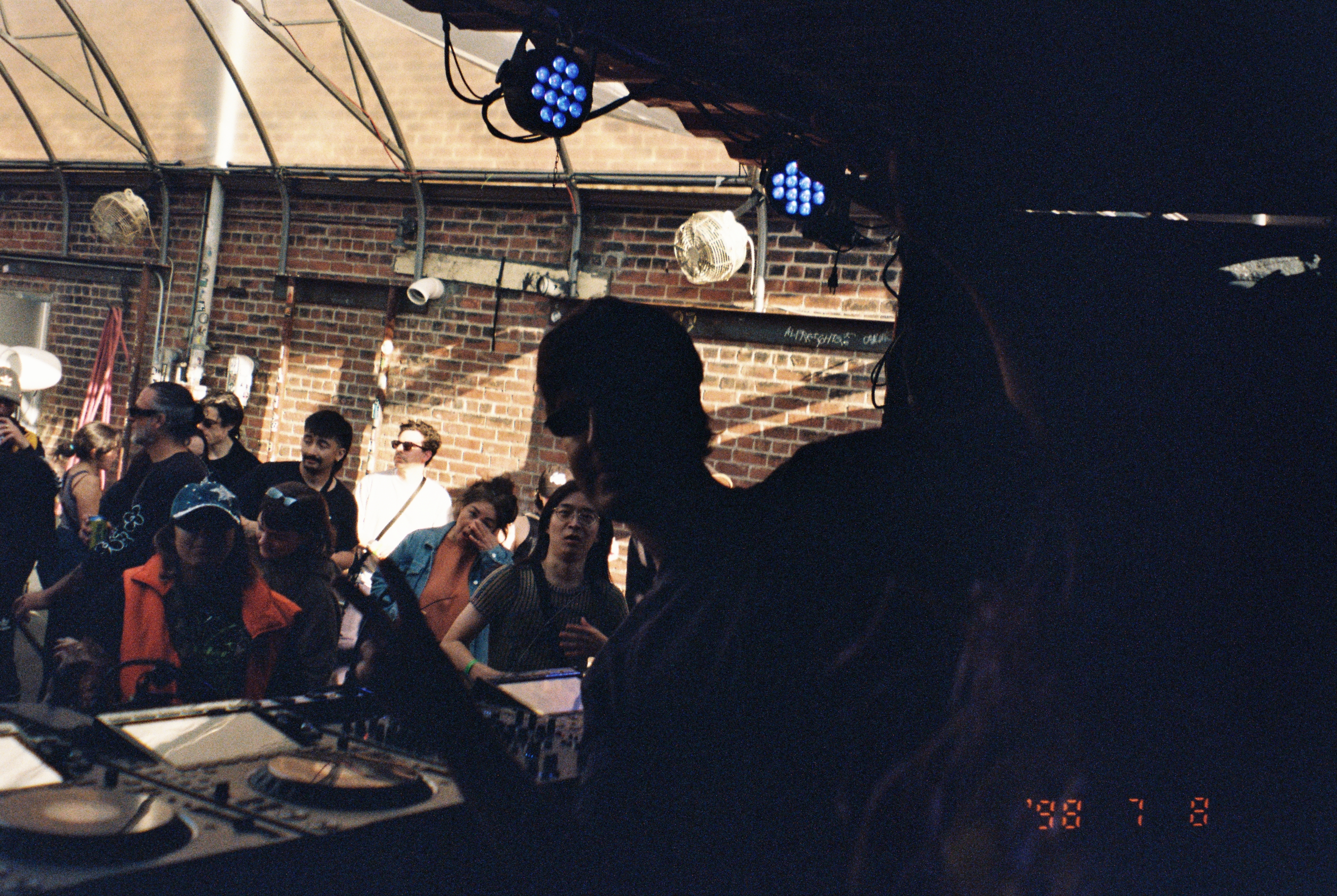

PICTURED: KIA B2B MOOPIE @ THE LOT RADIO, NYC. MAY 2024.

From experiences at festivals like Inner Varnika, like many of her peers, Kia grew a love for the DIY. Australia’s ‘doof’ scene has become increasingly popular and less easily defined as time has gone on. Inner Varnika would, to many, still constitute a doof even with its large-scale production and need to stay commercially viable.

However, much like the soul at the core of her label Animalia and Cirrus’ releases, Kia gravitated towards an intrinsic spirit at events like these, which had a profound impact not only on the music she absorbed but also on her outlook for the culture as a whole.

The idea of the ‘doof’ isn’t a new one. The term has entered Australian folklore with many an idea of where it came from, with perhaps the most persistent owing to an angry neighbour of Sydney’s Vibe Tribe, a punk DIY crew responsible for bringing trance records home to Australia after many an expedition to the iconic trance parties of India’s Goa region, requesting that they turn down the “doof doof” music.

While the politics of Goa’s trance scene have come under scrutiny in recent years, the freedom of creative, physical, and emotional expression associated with events like these found a fitting place in Australia, a country with its own complex history of how people treat, celebrate, and gather on its land.

The releases that Kia has spotlighted across Animalia and Cirrus, and that she plays within her own sets, are not songs that ‘tell’ the listener anything. To varying degrees, perhaps the one throughline across these, and Australia’s broader ‘prog-tech’ sound, is a psychedelia that invites curiosity in the listener, and with an undeniable ode to place.

Animalia is named after her favourite childhood book about animals. First started in 2020 with ‘Animalia One’, a compilation featuring her friends Ménage, Sam, and Jack Brickel, as well as Dashiell. The ‘Animix’ series, which had its 177th instalment, was also launched that same year, now accompanied by a live recording series.

The label’s discography now boasts homegrown talents regularly touring overseas, including OK EG, LOIF, Command D, Zara, Reptant, and al dente, as well as contributions to compilations by long-time friends Sam & Jack Brickel, Dashiell, Eugene Pascal and many more. In the early days of COVID-19, the part camo, part animal print covers of Animalia’s mix series grew with steady reverence. First featuring more of her extended friendship group, including Miscmeg, Dolly, Citizen Maze, Nino, and now featuring some of the world’s most revered producers and DJs.

PICTURED: Kia b2b Reptant @ Texture, The Marble Bar, Detroit. May 2025

Kia has, in the years since she first started, become a crucial mention in any conversation around Australia’s electronic music landscape.

Playing regularly at more closely guarded DIY events, her growing demand has not deterred her prioritisation of spaces, clearly paying homage to why she fell in love with the scene in the first place.

As much as the success of Animalia in particular has been undeniable, Kia is quick not to pigeon-hole what it or Australia does, saying that she “(doesn’t) agree with the general fixation on the idea that Australia's sound is this ‘progressive tech’ thing. I can see how a lot of the context of the last 20, 30 years of the music scene in Melbourne and Sydney and also beyond, suggests that, but I feel like there's a lot more to it.”

This respect for DIY has, most recently, culminated in her work on un:send, a collaborative festival co-run by her and a series of other collaborators, including duo OK EG, Kasun, and Dylan Batelic of Paper Cuts.

She is under no illusion that these spaces often sit at the outside of what more ‘mainstream’ dance culture is doing, but acknowledges that it is in these spaces where true experimentation, not only across music but in the engagement with social and political issues, is able to occur.

“You need things that fund the scene, and then you need the things that are at its core,” she mused. “The underpinning influences maintain its soul, underneath it all.”

For Kia, this soul takes many forms. Musically, further separating Australia’s ‘sound’ from the idea of a techy foundation are a series of her peers whom she credits with inspiring her and the broader Australian scene, not only here but on the global stage. These include the likes of “Steeplejack, A Colourful Storm, Efficient Space, Felt Sense, Moonshoe, Pure Space, General Merchant, to name a few,” though not being explicitly dance or electronic music. “That spans everything from folk to IDM, bass, techno, and trance,” she continued. “To me, it’s not about putting the ‘sound’ in a genre, but more how all these labels have this kind of Australian flavour, or how whoever is behind the label uses the context of their life to shape the music they’re putting out.”

For Kia, as a DJ and label head first and a producer, perhaps not even second, one of the biggest problems with the pedestal that DJs sit upon is the disproportionality with which producers are valued for their work.

Animalia started first and foremost as an outlet for Kia to platform the work of her friends, and the unfortunate irony that comes with her being so highly regarded for playing the music of other people isn’t lost on her. “I feel like there's this kind of weird DJ hierarchy, disproportionate attention towards deejays at the moment,” Kia pointed. “Producers actually have a really hard time because well, I mean, Spotify, etc… and when I’m throwing a party, I understand that from a promoter’s perspective, it’s more expensive and difficult and sometimes challenging to fit in a live set.”

“I'm hyper aware of being a DJ and the fact that being a DJ is a good position to be in,” she continued, “compared to all my friends who, honestly, I feel like I wouldn't be anywhere without. These are just my very talented friends who are usually really low-key people and maybe wouldn't otherwise put themselves out there.”

Kia is by no means a stranger to the production process. Outside of being involved in each release Animalia has put out from a curatorial perspective, in 2021, she released ‘Blue Rain’, a track via Dutch label Nous'klaer Audio.

“It took me like six months at a time to make one song when I was doing it,” she admits. “I've got my whole life. I'm not really in a rush. I feel like that's enough. I feel like there’s this feeling among DJs where they feel pressured to release music at some point, and sometimes, to me, it feels a bit rushed. I’m definitely keen to make music, but I want to make sure that when I put it out, it’s because I actually think it’s good and worth people listening to. Not because it’s the most important next step for me to remain relevant.”

When we spoke, Kia was back in Naarm after perhaps her biggest year to date in 2024. The artist, like many other touring DJs and producers, regularly uses Europe as a base to tour throughout the northern hemisphere’s summer months. Appearances at Dekmantel, Draaimolen, Sustain-Release, Monument, pe:rsona, Butik and a slew of gigs for much-loved local promoters and her own Animalia events filled her touring schedule to the brim last year.

While her commitment to and growing reputation among international events is undeniable, in our conversation, it was clear that she didn’t feel that striking a comparison between these and Australia’s offerings was doing anyone justice. “There’s a tendency to compare our scenes to the rest of the world, but it really frustrates me when people complain that ‘it’s so much better in Europe’ or ‘I wish we had what they have’, because we’re actually so lucky here,” she reflected. “Australia doesn't necessarily need to compete with or be compared to Europe, because I think when internationals come here, what they enjoy about Australia is the point of difference and that we've got our own thing going on and we're so far away.”

The idea of ‘soul’ within Australia’s electronic music may appear a long bow to draw. The trope of ‘connection on the dance floor’ so synonymous with often juvenile experiences of clubbing and festivals is something that, to many, becomes a given with enough exposure. While this kind of soul could be interpreted as the enthusiasm of vocal samples and profession of PLUR sensibilities, the soul evident within the music that Kia plays and platforms is one of reserved certainty. A sort of quiet confidence that, for many, has become a necessity to feel comfort and hope in the world around them, and to assist in finding like-minded people to travel it with.

In talking about Australian dance music, it could be easy to point this brand of confidence towards a ‘tall poppy syndrome’. With a wealth of experience across the globe, however, Kia makes particular mention of how this kind of contentment lends itself to an enthusiasm and support not always found in other scenes.

“Thinking about our world, and at least in the pocket that I exist in, it never feels competitive. I feel like everyone’s just really wanting each other to succeed. It makes you feel proud. It’s not dog-eat-dog here. A DIY approach pushes the promoters or the people putting the party together, and it also just enforces community because it takes a village.”

Compared with the vast, meticulous and world-class production attached to Europe’s festival circuit, to place such immense importance on the often crudely constructed foundations of Australia’s doof culture may feel inherently biased. In our conversation, Kia was all too aware of this frequently radical juxtaposition.

You wouldn’t really be out of context if you saw a photo of this barren, moon-crater-looking farmland, drought-ridden and filled with sheep carcasses,” she shared somewhat proudly. “A lot of them, from afar, wouldn’t look special, but that in itself has created a new culture of DIY, with different intents and added effort you have to put in for the party to be pulled off. There’s so much more risk, but there’s almost more reward.”

“More” reward is, much like the idea of music’s soul, hard to quantify. Kia is clearly under no illusion that her experiences in playing for those same world-class festivals and scenes have shaped her hugely, not only as an artist, but as a person. As she prepares to play Dekmantel’s 25th birthday this weekend, this comment, particularly with the benefit of hindsight, feels even more meaningful and entertaining in its juxtaposition.

The locations that house the doofs she loves, generally found by hardworking locals by way of being ‘friend’s farms’, campgrounds and properties owned by trusting and very willing lovers of music of all kinds are a crucial part of Australia’s musical ecosystem, it goes without saying that they are by no means the most huge gigs that an artist, particularly one visiting from overseas, may play.

Kia has, over time, established a vast network of personal and professional relationships with artists and label heads worldwide, regularly hosting the likes of Livwutang, Konduku, DJ Fart In The Club, Bitter Babe, Priori, and many other acts with a similar musical and personal leanings. While it may be easy for locals to assume that their regular bookings in Ibiza, Berlin, Amsterdam and New York City hold a larger cultural and professional value, Kia believes that in many ways, the doofs of only several hundred people often leave the most lasting impression.

“The outdoor festivals and raves that have been really influential here, and even the sets that leave a lasting impact, are usually done by locals. Locals have this really deep understanding of what the context provides… when you're used to playing in clubs or super, super established festivals, it would just feel different,” she balanced. “But if an international artist comes and they're lucky enough to witness that, it's really special. It's like a good way for an international to witness the true essence.”

This essence is, to many, tied to an acknowledgement of privilege that exists within so many of its participants, promoters and artists. Having moved interstate after completing her high school education and being able to prioritise music as a career, Kia is under no illusions about the privilege she experiences daily.

It’s in part due to this humility that Kia has been able to approach her understanding of the world as a global citizen while on tour. “To put it simply, I feel like I'm so insanely privileged to be able to travel the world that it would feel totally insane if I didn't do something to at least engage with the culture of the place I'm visiting,” she said with purpose. “I feel like it almost helps me with the gigs and tapping into connecting, and I play when I'm touring on a deeper level because it's a nice way of connecting with people when I'm travelling, understanding the context and the place better.”

Before she “accidentally” became a DJ as her career, Kia had studied politics and international studies with the intent to work as a diplomat. A look at her social media over the last two years, in particular, would yield insight into Kia’s involvement in the political roots of dance music, attending Pro-Palestine rallies hours before a much-anticipated club gig, advocating for the needs of First Nations Australians, and sharing crucial political articles and perspectives via her social media stories.

The highly politicised nature of dance music, particularly in a modern geopolitical context, is one that often demands critique from everyone involved. Increasing investment by private equity and ‘big business’ in dance music and live music has forced the hands of artists, who are now not only playing gigs but, in some cases, being compelled to advocate for them. For her, this has meant that “things do feel like they're changing, but I feel like the cultural changes that are coming are inextricably tied to the rising cost of living, and just life being more expensive, things being scary politically, not just like in Australia, but worldwide.”

In a local sense, Kia points to Australia’s history as a means of better dealing with these kinds of changes. “We live in a colony. It's a really new country, and we're all settlers here unless we're indigenous, which I'm not. And so the answer to, you know, our music scene, changing for the good is first and foremost just acknowledging that.”

It’s in this climate of change and rising conservatism that Kia feels that the underground is most at risk.

“I just hope that the DIY scene, the underground, manages to survive. Sometimes it seems to stray. But yeah, generally I just hope that it can stay alive.

“DJs can't save the world,” she admits.

The landscape of dance music has undergone drastic changes since Kia and Animalia entered the scene, and this evolution has accelerated significantly over the last two years. DJs may not be able to save the world, but they’re regularly turned to as a paragon of desirability and ‘coolness’ in a world increasingly obsessed with both.

The concept of relevance was one that our conversation frequently returned to. Kia herself admits that she is no longer part of the newest generation of Australia’s artists. She approached the idea of TikTok techno with a feeling of slight fear and depression, as well as the need to utilise social media to gain recognition.

Irrelevance, however, is not something that fazes her. “I don’t agree with this old school, gatekeeping or boomer attitude of purism, or vinyl only,” she declared, but hoped that people would continue to “pay homage to the people that built our scenes around the world.”

The idea of Australia’s ‘sound’ is one entirely based on this same brand of relevance. To dive into conversations around why a certain sound prevails over all others is a topic that, for a music journalist, can define careers but may ultimately have little meaning at all.

Did Kia and Animalia contribute to shaping our sound in this direction, or does Kia's presence as an artist stem from the multitude of factors that led to Australia being in this exact moment?

Brian Eno is, among many things, credited with coining a term for questions like this. The idea of ‘genius’, he shared alongside also prompting listeners not to get a job, is “a process of singling out certain people in art history and saying ‘those were the important ones.’” Instead, he argues, the idea of genius is actually the result of a very active and flourishing cultural scene. For this reason, perhaps his term, ‘scenius’, is more appropriate than a series of hypothetical questions.

For Kia, however, such questions don’t appear to matter much.

“I just feel like I don't really deserve the attention,” she shared, clearly not for the first time. “It's all the people I've worked with through the label who have built this ecosystem. Maybe it’s one thing putting Australia on the map, but I don't want it to be the defining thing, and I don't think it is.”

This humility is at odds with much of what comprises the conversations surrounding DJs. Big teams, big release schedules and big shows are part and parcel for so many of the world’s more revered artists.

It’s at this point where you, the reader, may wonder at what point in Kia’s promo schedule this feature is meant to sit within. While un:send does appear to be on the horizon, there’s no massive tour, no specific Animalia release to speak of, and no music on the way. Instead, this conversation with Kia could likely sit at any point in her career.

In a moment where dance has never been bigger, where being a DJ sits as one of the biggest pieces of cultural capitol that someone can aspire to, and where there’s never been more money in the industry that surrounds it, what sets Kia apart now, before and into the future, is the soul with which she approaches it.

The soul is evident across the music she platforms, the way in which she plays it, and the acknowledgement of everything that contributes to it.

She is, after all, just one person.

“The whole thing was a bit of a fluke,” she laughed. “I started the label for fun with absolutely no knowledge or idea of what I was doing. I was just listening to my really talented friends make music in their Coburg backyard studios, and an idea was proposed to me to start the label when I was playing a lot of unreleased music. I’m not a businesswoman, and much of my DJ career has been me digging myself out of label debt.”

Q: If you could be an animal, what would you be?

“I think I would be a bird, but I don't think I'm elegant enough. I mean, if I want to survive, I’d probably be an eagle, but I don't think I'm an eagle.”

-

Jack Colquhoun is Mixmag ANZ's Managing Editor, find him on Instagram.