FEATURES

FEATURES

The quiet legend of Micronism

Writer Martyn Pepperell explores the legacy of an artist whose influence is felt not only across Aotearoa, but the world today.

When Denver McCarthy, one of Aotearoa’s most respected electronic musicians, released his debut album Morningstar (1994) as Mechanism, he was already operating on a higher frequency. That year, in a testament to the industrial techno he was producing, Mechanism’s Forever I Fly South EP surfaced internationally through IST Records (US). Near the end of the second half of the ‘90s, McCarthy’s sophomore album, Inside A Quiet Mind (1998), arrived under a new alias, Micronism. Across its eleven tracks, he swapped his brutalist beatscapes for leafy biophilic architecture and sweeping synthesised vistas, reimagining his music as a heady convergence of ambient dub techno and ecotechnological electro.

As the 21st century dawned, CD copies and mp3 rips of Inside A Quiet Mind began incrementally working their way into the hands and hard drives of techno fans across the globe, winning over hearts and minds. Resultantly, by the mid-to-late 2010s, McCarthy's critical reputation had received a boon via reissues of his late ‘90s work through the Delsin and Loop Recordings Aot(ear)oa labels. The most notable was Loop’s double-LP vinyl edition of Inside A Quiet Mind, described by Bandcamp Daily’s Su Baykal and Resident Advisor’s Angus Finlayson as “...a universe of energy and lightness” and “a record that captured a life in transition” respectively. For reasons that will soon become apparent, these two assessments were fitting.

Six years later, McCarthy was awarded one of New Zealand music’s highest cultural accolades in recognition of Inside A Quiet Mind’s legacy, the Taite Music Prize 2023’s Independent Music NZ’s Classic Record Award. By then, he was on a new journey that began when he joined the Hare Krishna faith in the late ‘90s, before spending the early 2000s in South America and eventually settling in Australia. These days, he lives in Meanjin/Brisbane with his wife and young son, where he works at a Hare Krishna restaurant and helps run Kirtan (collective chanting) workshops.

CREDIT: MARC ROSEWARNE

Born in Tokoroa, McCarthy spent his childhood in Mount Roskill, a multicultural suburb in Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland, the largest city in Aotearoa. By age eight, he’d got his hands on a borrowed Casio Keyboard and seen the classic American hip-hop dance drama Beat Street (1984). A lifetime later, he has vivid memories of playing the keyboard for hours and being floored over by the American music, fashion and breakdancing depicted in Beat Street. When the British electro artist Paul Hardcastle’s anti-war anthem ‘19’ (1985) went to number one on the New Zealand Pop Charts, he was paying close attention to Hardcastle’s production and sampling choices.

In 1987, McCarthy picked up an acoustic guitar during his first year at high school. After getting an after-school job, he saved up for an electric guitar and joined his first band, Blueprint, followed by the heavy metal group Power Jelly. As with many New Zealand techno and drum & bass producers of his generation, his pathway towards electronic music began in rock, metal and industrial. It’s a distinction that often differentiates them from their North American, British, and European peers, who arrived from hip-hop, dub reggae, and rare groove scenes before embracing the machine beat.

During high school, McCarthy started attending warehouse raves, where he was exposed to the emerging sounds of the early ’90s UK and US underground. Alongside these foundational experiences, he shopped at Takapuna’s Truetone Records. McCarthy remembers an influential record store clerk named Alec Coleville slipping him xeroxed copies of DJ Heather Heart’s New York rave fanzine, Under One Sky. Inside those black and white pages, he found a window into a bigger world.

Bitten by the bug, McCarthy dropped out of school and started working at a local musical instrument store, Kingsley-Smith’s Music. That job gave him access to the latest drum machines and keyboards. As he told Henry Oliver for The Spinoff in 2017, “I would tinker away on the synthesisers there and my interest just pulled me more and more into working out how to use them and trying to express my ideas through them. And slowly, I learnt more. I was quite driven, actually.” That wasn’t all. Kingsley-Smith’s Music also placed him near a Hare Krishna restaurant he’d visit for cheap vegetarian meals.

Later on, he’d be looking to Krishna for more than lunch.

From there, McCarthy befriended a community of producers and DJs from Tāmaki Makaurau and Kirikiriroa/Hamilton. Operating within the Venn diagram overlaps between techno, industrial, jungle/drum & bass, and ambient music, this milieu gave rise to a range of crucial figures, including Ben Harris aka System 100, Jared Sims aka J Red, and DJ Aaron.

Once they’d established common ground, McCarthy and Sims began recording and performing live techno sets together as Plankton & Skrimshank. Martin Kwok, aka Dan Aikido, an Emmy award-winning sound editor and longstanding DJ from Te Whanganui-a-Tara/Wellington, remembers their demo cassette making its way to him via Alec Coleville. A couple of the songs piqued his interest, and he started playing them on the local student radio station, Radio Active 88.6 FM (then 89 FM). Several months later, Kwok and his friends headed to Tāmaki Makaurau, where they were impressed by what McCarthy, Sims and Aaron had to offer. “Denver [McCarthy] came with DAT tapes of his own music, which sounded like nothing else,” he says. A budding kinship led to both crews hosting each other in their respective cities.

In the early to mid '90s, McCarthy flatted with Ben Harris. Back then, Harris helped run the cult Karangahape Road coffee shop Brazil. Later, he founded the esoteric, brilliant and underdiscussed CD record label, SYSTEMatic Recordings. Harris remembers McCarthy as having a tranquil persona and broad music tastes. They would often swap production tips and equipment. One night, they even recorded an improvised electronic jam, which Harris describes as straight-up synth jazz in the style of Eric Dolphy. Years later, he released it through SYSTEMatic as Liquid Water.

Serendipitously, McCarthy’s breakthrough came when New York’s Leonardo Didesiderio, aka Lenny Dee, DJed at an influential Tāmaki Makaurau nightclub of the era, The Box. Still only seventeen, McCarthy brought a DAT machine and his demos to the party. Impressed, Didesiderio signed Micronism to his label, IST Records. For Kwok and the Te Whanganui-a-Tara techno crew, ‘Good-Morning’ off Micronism’s IST released Forever I Fly South EP (1994) was a moment in time. “I have many memories of dropping that record at key points in a night and watching the whole place build and dissolve into a state somewhere between confusion, submission and euphoria,” he remembers. “By the end of the track, it was like being in orbit, looking back on the beauty of our little blue planet.”

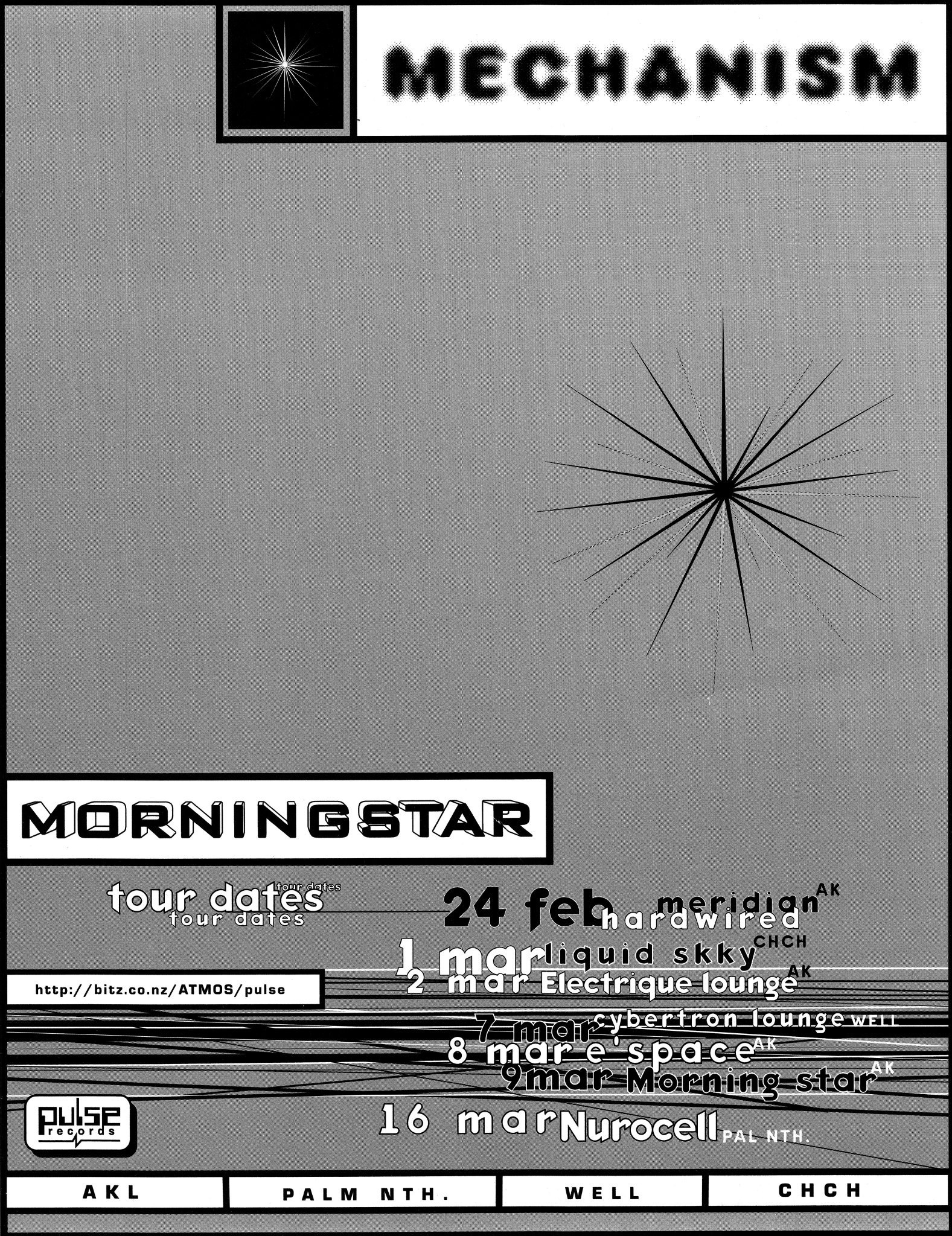

Alongside Didesiderio and IST, McCarthy benefited from the support of the multimedia artist Mike Weston, who was operating an alternative arts hub called Cyberculture with Heath Burgoyne. Weston ran a short-lived label, Pulse Records. Pulse’s first release was the early New Zealand techno compilation Harmonic 695, which featured two Mechanism tracks and ‘Viaduct’, which McCarthy co-produced with Weston as Pedestrian. Its second project was Morningstar. Created on a Korg 01/W workstation synthesiser, the album was a hefty blend of melodic industrial techno inspired by heavy metal and McCarthy’s experiences with psychedelic drugs and the Christian faith. Fitted with titles like ‘Destroying Angel’ and ‘Celestial Fall’, Morningstar’s ten tracks felt like a hurricane tearing through a sprawling futuristic cityscape.

Following his Pulse and IST releases, McCarthy DJed and performed more around Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. Beyond Tāmaki Makaurau, nearby Kirikiriroa, and Te Whanganui-a-Tara, he was embraced further south in Ōtautahi/Christchurch. Simon Kong, a longstanding figure in Te Waipounamu’s dance party and outdoor rave culture, remembers seeing Mechanism play the legendary, long-shuttered Ōtautahi nightclub Ministry during the mid ’90s. “Morningstar was the first New Zealand-made techno album that blew me away,” he says. In his head, he was anticipating a “hard cut dark edgy techno person”, so he was surprised when McCarthy brought a chill presence and a big smile to the stage. Thinking back, Kong remembers him, in the style of ‘90s Goa DJs, using two DAT machines to showcase his productions.

As the decade unfolded, Mechanism scored a second 12” vinyl release through IST Records in 1996. The following year, he contributed a track as Chaos Reader to AK97, an electronica compilation referencing the classic Tāmaki Makaurau punk compilation, AK79. Leading up to AK97, he connected with a new generation of local techno, breaks and digital dub heads who congregated around the Kog Transmissions artist collective and then newly minted Nurture label. Within this milieu, McCarthy met a young Māori DJ and producer named Tiopira McDowell aka Miso, and helped him record his first drum & bass tracks. Over two and a half decades later, McDowell, now known as Mokotron, is an award-winning artist and a central figure in the rise of the Hiko (Māori electronic music) movement.

PICTURED: DANCE PARTY AT 398, TĀMAKI MAKAURAU/AUCKLAND

At the time, Kog was running warehouse raves at 398 Great North Road in Grey Lynn. When their de facto leader, the musician, producer and audio engineer Chris Chetland, realised McCarthy was living nearby, he invited him to the studio. Not long after, he extended the offer to release an album through Kog. Having been big fans of Morningstar, Chetland, and Kog, they were expecting more of the same, but that wasn’t to be.

“When Denver [McCarthy] turned up with a super quiet, ambient techno album, we had to pivot conceptually,” Chetland admits. After listening to the first few tracks, they were sold. Sensing a sea change in the global techno landscape, he stepped away from Mechanism's dark, abrasive and high-tempo sound, adopting a more sophisticated and atmospheric style in the mode of Jeff Mills, Basic Channel, Underground Resistance and Drexciya. We’re talking about music that hits the sweet spot between genuine human emotion and analog circuitry, man-machine interfacing rendered through robot grooves dripping in uncut funk.

In tandem with his aesthetic shift, McCarthy was experiencing an internal rebirth. He still liked those plates of cheap Hare Krishna food. Increasingly, however, they went hand-in-hand with meditation, spirituality and Kirtan, a form of call and response mantra chanting that reaches into the infinite. “The spiritual aspect of Kirtan makes it fresh every time you do it,” he explains. “It’s about the presence you bring to it.”

Once Kog had digitised McCarthy’s DAT tapes, they spent a frantic week denoising the material and mastering it on a malfunctioning computer. Simultaneously, McCarthy worked on the CD artwork with the graphic designer Pat Hammond, while preparing for the release party at the long-shuttered Herzog venue on Karangahape Road. “Because we had no money, we all sat in the lounge and put the artwork and CDs into the jewel cases by hand,” Chetland laughs.

The result was Micronism’s Inside A Quiet Mind, described by Whakatū/Nelson journalist Grant Smithies as "the best electronic album ever made in this country". Eighteen years later, it remains a high-watermark for New Zealand techno. Opening with the crisp, naturalistic vistas of ‘Constructing Space’ and the shimmering chords and slow-burning pulse of ‘First Reflections’, it offers the utopian promise of a future where nature and technology coexist in balance, offering up clean blue skies, pristine ocean waters, and lush, leafy landscapes.

In keeping with Morningstar, part of what distinguished Inside A Quiet Mind was McCarthy’s ability to hide composed song structures inside functional dancefloor weapons. Whether listened to as an album or deployed within a DJ mix, his work shines brightly. These qualities come into sharp focus on ‘Rainbow City’, a red-hot electro track driven by dynamic synthesiser lines, punchy drum machine patterns and a wormy p-funk bassline. After taking the coastal route through several elegant ambient techno explorations, McCarthy shows off yet more refined dancefloor sensibilities on a dreamy number evocatively titled ‘engaging causeless mercy’. From there, the album pulses, ebbs and flows towards a stargazed conclusion on ‘Steps To Recovery’.

A year later, the Nurture label pressed several tracks off Inside A Quiet Mind as a 12” vinyl EP titled Steps To Recovery (1999). In the process, they helped further McCarthy’s mythos, both at home and abroad.

When Simon Kong heard about McCarthy’s transformation from Mechanism to Micronism, he was intrigued. Broadly speaking, while Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu’s dance communities were still shoring up their foundations, McCarthy was already evolving. Decades on, Kong sees him as a leading light in a generation of New Zealand techno artists who used ambient and dub sensibilities to evoke the grandeur of the country’s natural landscape and the deeper undercurrents of the scene. “When I reflect on Denver [McCarthy’s] music, I feel like he came into the scene and gifted us with something timeless,” reflects Kong. “More importantly, he showed us a different path, a different idea of what we were perhaps all looking for.”

For McCarthy, that began in earnest after Inside A Quiet Mind. “I had this Hare Krishna record with the founder of the movement, Srila Prabhupada, chanting on it,” he recalls. “I just remember there was a period when the only thing that was of interest to me was listening to it. I guess quite quickly, I lost my taste for listening to techno music and going to parties.” As he transformed, life led him to a Hare Krishna ashram in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, where he pursued meditation and philosophy.

Leon Dahl aka Leon D, a Tāmaki Makaurau-based DJ and producer who spent the early 2000s in the house duo Cuffy & Leon D, remembers hearing stories of McCarthy using a Roland TR-909 drum machine to provide a backbeat when his Hare Krishna group were chanting on the streets. I thought this might be an urban legend. However, Martin Kwok recalls running into McCarthy and accepting an invitation to visit the ashram for a meal. When the devotees started chanting after dinner, Kwok got a surprise when a punchy Roland TR-909 machine beat joined the hand drums and percussion. “Denverism was still very much in the building,” he says wryly.

In 2000, McCarthy relocated to South America, where he lived at temples in Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, while practising Bhakti yoga. In another timeline, this could have been where his musical story ended. However, as he faded from view within Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu’s electronica scenes, his music continued to flow outward.

Inside A Quiet Mind was McCarthy’s first and only Micronism album, but it wasn’t his final work. Before 2000 was over, New York label Statra Recordings had released his third album, Rise And Shine, this time as Denver McCarthy. Splitting the difference between Micronism-style techno, ambient breaks and South Pacific synth-funk, it feels like a hidden gem within his discography. The same can be said for his little-known second Mechanism album, Fall of the False Self, a fierce collection of unreleased industrial techno from the mid-'90s, which McCarthy quietly uploaded to Bandcamp on December 12, 2024.

It doesn’t stop there. During the 2000s, three more Micronism and Mechanism EPs surfaced on 12” vinyl, as well as several projects McCarthy recorded in South America, mixing Kirtan mantras and electronica as DJ Vraj. Ultimately, those productions were intended as a tool to help Hare Krishna youth stay engaged with the movement’s spiritual practices. Equal parts devotional and downbeat, his Antimateria EP (2006) still embodies something special, nineteen years on.

When asked to reflect on his early music, McCarthy pauses for a moment. “It was strange how the title 'Inside A Quiet Mind' foretold something about my future,” he continues. “I was just getting into meditation and tinkering with ideas. For some people, music can give them a hint about their future. I wrote a whole bunch of music with Latin American percussion samples that never really got released. You can hear a little bit of it on 'Rise And Shine'. Not long after, I was living in South America, the land of salsa.”

PICTURED: DENVER MCCARTHY STUDYING AN ASHRAM LOOP RECORDING

Today, McCarthy helps run Kirtan workshops across Meanjin to promote the mental and physical health benefits of group chanting. “We have Kirtan every day at the [local] temple, but I’m part of a team that organises Kirtan for people who would never go to the Hare Krishna temple,” he says. “We do these nights where we present Kirtan as a musical, meditative healing experience.”

In recent decades, a new generation of Western Kirtan singers has weaved contemporary influences into the tradition. McCarthy is in the mix here as well. Earlier this year, he toured Australia and India playing bass for Jahnavi Harrison, a well-known British musician who reimagines kirtan with classical, Irish folk music, and gospel flourishes, bringing the spiritual practice to ecstatic gatherings. “The addition of Western musical instruments has opened Kirtan up to a wider range of people,” he explains. “When we were in India, we’d have audiences of fifteen hundred people chanting back. It was a dream come true for me to be able to help present Kirtan in such a musical way.” You can view some documentation from this tour on his Vraja Music Instagram page.

From playing guitar to inspiring Aotearoa’s ‘90s rave generation, finding himself through selflessness, and now participating in a new era for Kirtan music, McCarthy has lived many lives in one life, navigating from chaos to calm with studied grace. He’s been lucky enough to be a vessel for greatness while coming to an understanding of the power of doing it together. To quote his acceptance speech at the Taite Music Prize 2023 award ceremony,

“I’m made of the kindness of all these people I’ve mentioned. A flower grows because of the environment it is given, and because of all of these people, I feel so grateful and indebted. This reward will serve as a reminder of their kindness to me. Thank you so much.”

-

Martyn Pepperell is a freelance journalist, copywriter, broadcaster, photographer and DJ. Find him on Instagram.