FEATURES

FEATURES

More 'place' than 'piece' on Climes' 'Water & Music'

The Gadigal Land/Sydney producer's debut album, paired alongside a full-length album visualiser by Naarm/Melbourne filmmaker Jordan James Kaye, is an ode to humanity when we've never needed it more.

In an era where documenting our own lives may, to some, appear as curation, it’s never been more difficult to separate perception from intention. Art is, whether we like it or not, more of a product now than it’s ever been, used by many as a means of unlocking opportunities, financial, social and spiritual.

As far as a music publication is concerned, discerning between what is truly real, what is exciting and what is not, has only become more difficult. Who are we to ask, at first glance, whether someone’s art is legitimate?

But for some, creating art is not a choice they consciously make. Their work, the way they view their reality, how they interpret their emotions, and how they choose to make their voices heard are as persevering as the water that runs across our world.

For Monty Callaghan, a Gadigal Land/Sydney-based musician and artist also known as Climes, that analogy is not only poetic, but a driving force behind his debut album, ‘Water & Music’.

As much an experimental composition as an ambient work, the record draws on a range of strings, pads, and archival recordings to create a post-classical piece almost entirely without percussion. Not someone who would be quick to describe himself as a regular contributor to the musical fabric of his hometown, Monty’s debut comes from a place of an arguably more genuine desire for creation.

The catalyst for the album came a number of years ago, when Monty discovered some old cassette tapes of his father’s, recordings of his mother, Monty’s grandmother, playing the piano around forty years prior.

“A fierce and charismatic Irish woman, my enduring memory of her is her perched upon her pale green recliner, cloaked in a drifting cloud of B&H Smooth cigarette smoke, with a frosty glass of lemonade and a crossword at hand,” Monty shared.

Shortly after that experience, Monty found another recording, this time on his maternal side: his mother’s mother’s vocals, recorded between 1998 and her passing in 2011. “A lover of old standards, opera, and choral music, one of my earliest memories is of her breaking out into song at a family gathering. I think I had just woken up; the light low, no one next to me, and the sound of her voice soaring in through the walls from the next room,” he reflects.

Finally, during a short time spent living in Berlin just prior to COVID-19, Monty recorded his Reykjavik-originating friend Sölvi Kolbeinsson playing saxophone in his attic, “for no particular reason.”

As Monty continued to play with each of these recordings, “those recordings with Sölvi revealed themselves as a thread that could tie us all together, binding an unlikely quartet into a tapestry of sound across time.”

In this way, ‘Water & Music’ is a project that begs to be listened to in its entirety. Whether in the way a piano is played or a song is sung, there is an objective kind of sentimentality that runs through its near hour-long run time, and provides a refreshing and earnest alternative to many of its local peers.

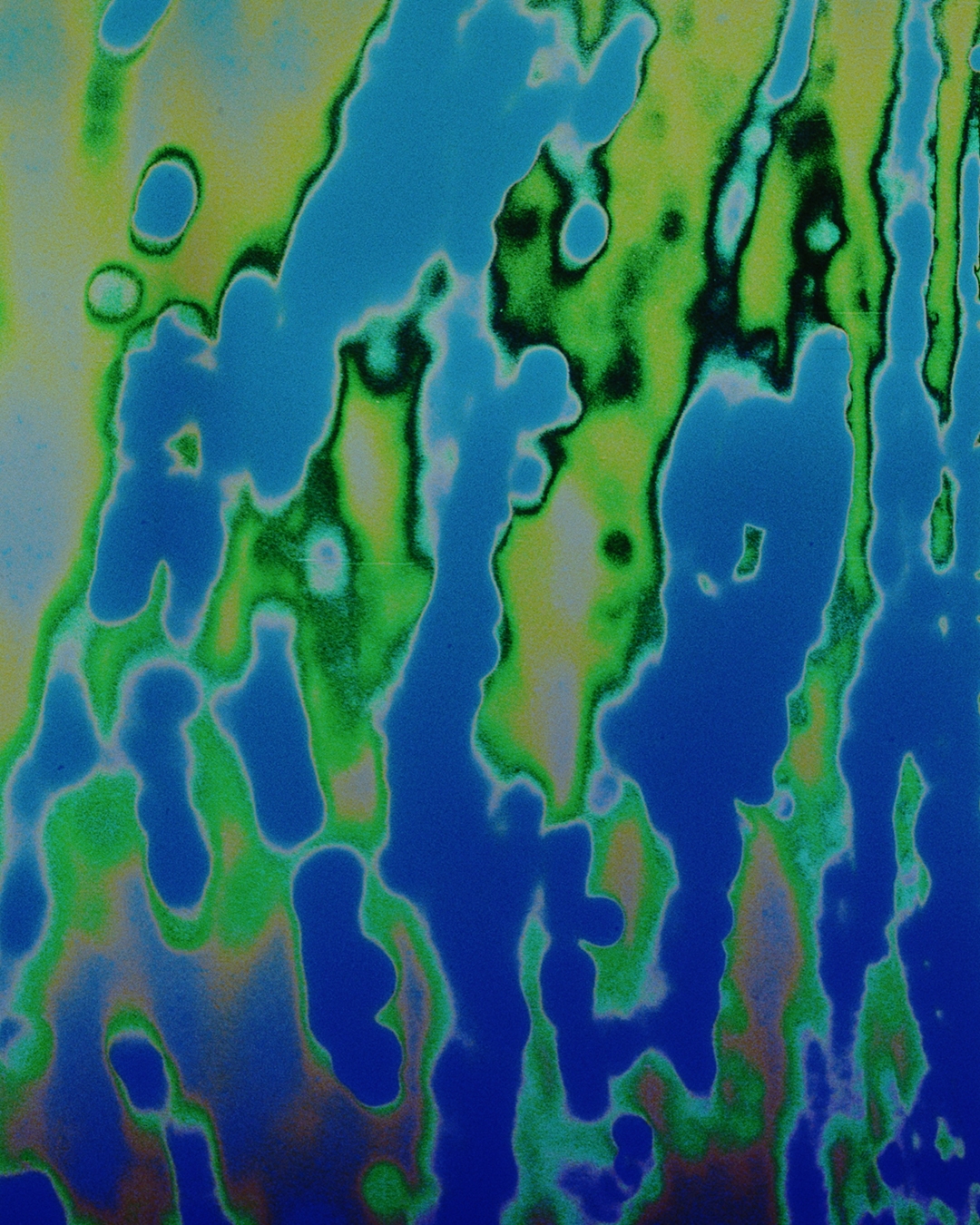

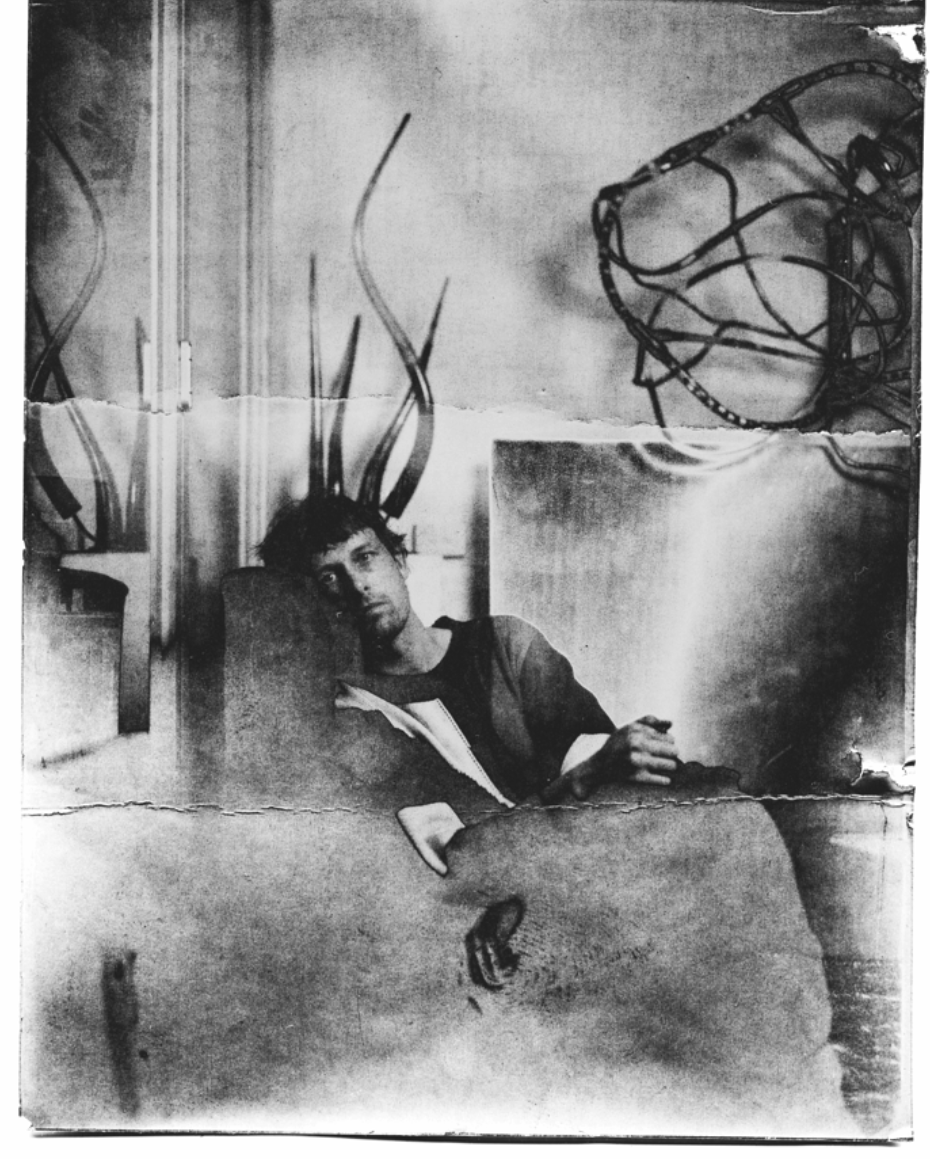

Released in tandem is a full-length album visualiser, shot, directed and edited by Naarm/Melbourne-based filmmaker Jordan James Kaye. Much like the album, Jordan’s visualiser oozes with nostalgia for a time many of us never lived through, achieved through modern means.

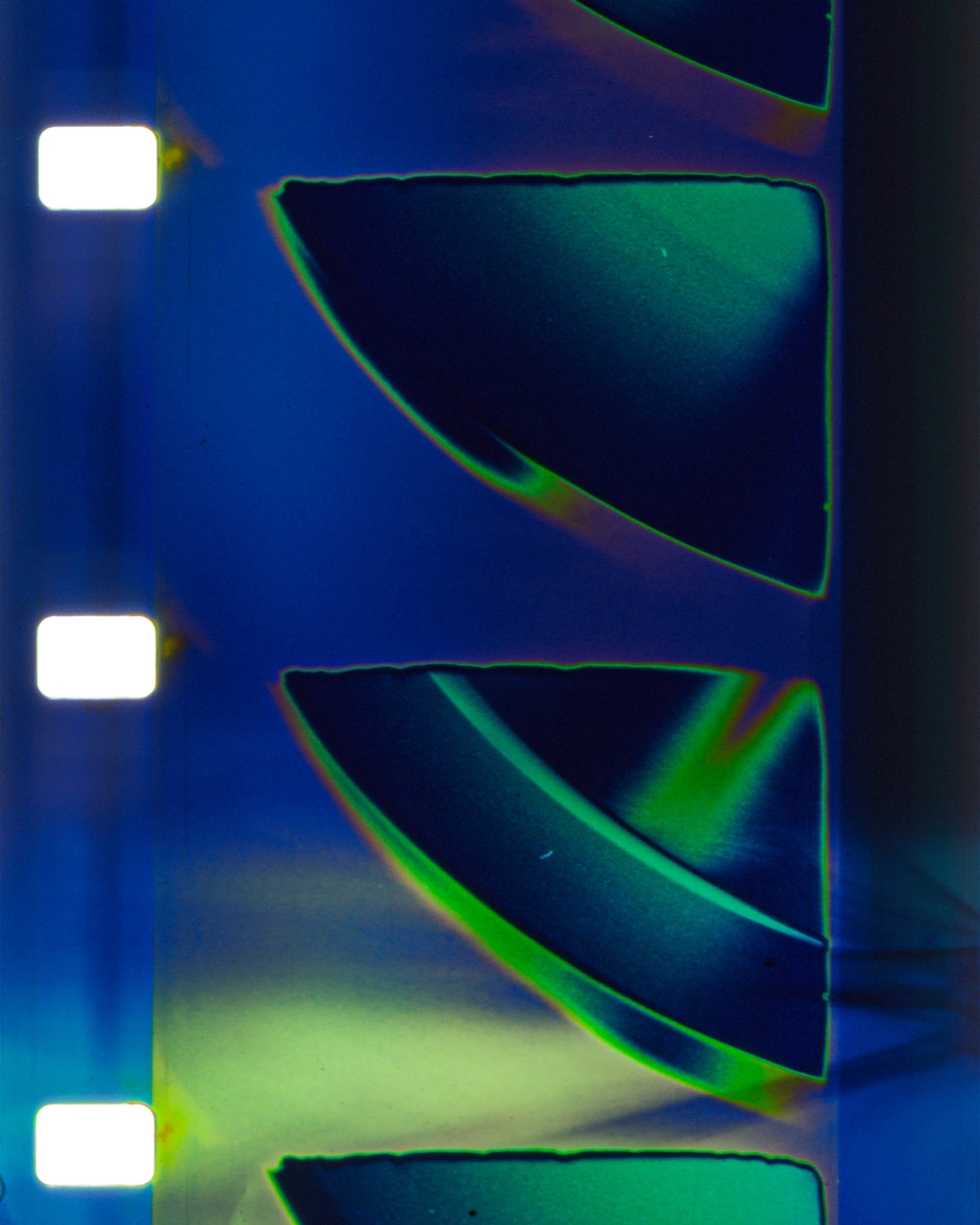

Throughout, he’s interpreted ‘Water & Music’ using a technique developed at the Artist Film Workshop he embarks on yearly. 16mm film, not meant for use inside film cameras, has been exposed and used in a way that blurs each image together in a way very reminiscent of water itself. Shots of waves, forests, and gravestones, along with archival photos, suggest a story we can only interpret, but never truly know.

Across both the film and Monty’s album, we come to miss people we may never have truly known.

In pursuing that feeling, both have reminded us that humanity is there, at a time when we’ve never needed it more.

To celebrate the release of ‘Water & Music’, we caught up with both Monty & Jordan.

Q: Monty, thanks so much for taking the time to chat with me. Firstly, I wanted to ask a somewhat generic ‘music journalism’ interview question. Generally, someone’s first album is a moment met by a lot of PR training, anticipation and a kind of planning akin to a job promotion, rather than the finalisation of a piece of art. ‘Water & Music’ isn’t the kind of album that these sorts of conversations are had around, generally speaking. So, what does this moment feel like for you?

MC: Pleasure to talk, Jack. It’s a cool moment, one that’s been quietly building for a little while. The feeling is mostly one of relief and letting go, but also a touch of intrigue about how it settles into being.

Q: I had the pleasure of listening to quite a lot of this record at your debut live performance in November of last year, supporting American producer Huerco S. It’s the first time, however, that I’ve seen it written about or promoted, which I often find is an interesting insight into the way someone ‘presents’ their work, outside of the stage. What has it been like trying to capture this record in words?

MC: Yeah, it’s probably not a record best captured by words – at least not from me. I wrote a few about making it, but hopefully the music and the film will slowly arrive where they’re meant to be without needing context. The Huerco S. show was a perfect way to begin that – just bringing it into a space and allowing it to breathe.

Q: The record is informed, and in some way given a narrative, by a series of archival recordings of your grandmothers, mothers to your father & mother respectively, not partners, it should be noted. At what point did you move from appreciating these recordings to working with them? What in them inspired you to do so?

MC: It was a pretty immediate process, actually. The afternoon I found the tapes of Pat (my Dad’s Mum) playing the piano was the afternoon I first began working with them. They had a haunted, ethereal quality that I was very excited to dig into and dissect. It was wild knowing my Dad was younger than the person who captured that moment in time more than 40 years earlier. I discovered Carmel's (my Mum’s Mum) vocal recordings only a few days later, and it was clear I should explore bringing them together.

Q: As I understand, your grandmothers both passed when you were still quite young. If you don’t mind my asking, what has it been like to interact with sound that you feel you ‘owe’ emotion?

MC: Yeah, I didn’t really know them – not in a fully realised way, so spending all this time with these momentary fragments of their life was powerful. Of course, you become conditioned to this pretty quickly, but from time to time, there were moments when the gravity of the recordings and the history and memory attached to them would hit you. I had only one opportunity to preserve them in a record, so I felt compelled to take the time to do it properly.

Q: In lightly discussing the album recently, you told me that “their memories are channels with which to explore ‘that kind’ of feeling.” What is “that kind” of feeling to you?

MC: At the risk of cliché, I’d have to say it’s probably the passage of time, and the whole spectrum of life caught up in it – endlessly running the gamut and turning back in on itself. Memories, both real and imagined, bring that feeling right to the surface.

Q: There’s a real, objective sentimentality on this album, which I find incredibly interesting given the record's context. Why do you think music like this lends itself to appearing ‘sentimental’?

MC: A friend was joking that I’m delving into the genres of #archivalambient and #ripmusic, which I’d have to say is objectively true. There’s no getting around the fact that dealing with these themes is sentimental territory, but it felt honest and real to embrace it. I think using tape as a sound source can also evoke sentimentality and nostalgia.

Q: I understand that you’re hugely inspired by American composer William Basinski, & in recent years have even developed a friendship with him. How did that come to be?

MC: Yeah, William has been a towering influence and a deep source of inspiration. It’s hard to imagine life without his music. I met him at a show years ago when I was living overseas, and have been lucky enough to spend time with him and to keep in touch ever since. To me, he is one of the great artists of his generation – truly a giant of music – but he’s also just a magnificent person. I’m very grateful for his friendship – his generosity has been amazing.

Q: Basinski’s 2003 piece, ‘Watermusic II’, appears to be a clear point of inspiration for the title of this record. What is it about his work that’s affected you so deeply?

MC: It definitely opened a third eye (or ear) for me. I’d never heard or experienced anything like it. It’s always felt more like a place than a piece of music – something suspended outside of time, with no beginning or end. That sense of timelessness, and of the ability of sound to portal into it, was very profound for me. I don’t think my album gets anywhere near that feeling sonically, but conceptually, it was probably a big influence on how I framed it.

Q: Water is a constant not only in the title of this record but also sonically. There is a large variety of recordings of water sources here, & the cover itself appears as a kind of celebration of it. What is it about water that has it placed so centrally & thematically here?

MC: Water is pure life force to me. I’m someone who gets excited by the rain and finds a thunderstorm is often a peak listening experience. The sound properties of water are endlessly fascinating; no two recordings of it are ever the same, yet they all share this universal essence of life force. Having this brush up against the deeply human act of making and performing music became an interesting angle.

Q: I feel like there’s a clear parallel between the recording of those water sources and your use of archival recordings of your grandmothers. Life is, both as an analogy and otherwise, like water. Are the sounds we make, the music we produce, like water, to you?

MC: In a sense, yes, there’s absolutely a parallel between them. I think maybe the album is trying to place a mirror between the two.

Q: It’d be remiss of me not to acknowledge Icelandic saxophonist Sölvi Kolbeinsson, whose work features across the entire record. How did you two become familiar, & how has his work stayed so deeply in ‘Water & Music’?

MC: I met Sölvi when I was living in Berlin through our dear mutual friend Madeleine Brunnmeier (who also took the album cover photograph). He had moved from Reykjavík to study jazz, and he agreed to let me record him playing in the attic of the building I lived in. I was asking him to play in ways very different from his usual style: long, sustained notes, repeated arpeggios, and generally trying to extract the harmonic and tonal qualities of the saxophone as a sound source. When I started putting the album together a couple of years later, it suddenly occurred to me that these recordings would be a cool counterpoint to the sounds I was already working with.

After this, I knew I could finish an album.

Q: Finally, we need to discuss the accompanying film, a hand-shot and edited 16mm visualiser spanning the album’s length, made by Naarm/Melbourne filmmaker and artist Jordan James Kaye. How did this collaboration come to be?

MC: I met Jordan at another dear mutual friend, Thorsten’s 30th birthday celebration. We got along well, and I gradually became familiar with his amazing work. After I finished the album, I finally plucked up the courage to pitch the project to him. We began a lengthy email exchange, which we’re hoping to reach the 100-email mark at some point, and started scheming. The second time we hung out was when he flew up to meet me to shoot the film for a couple of days. We’ve become very close since.

Q: In normal circumstances, a visualiser adds an emotional extension to a work. Throughout Jordan’s film, however, images, textures and colours are obfuscated in a way that gives it an ethereal quality, not firmly rooted in any particular place. How do you think this adds or extends upon ‘Water & Music’?

MC: Yeah, this is exactly why I was so blown away and moved by what he created. I don’t know how he interpreted the music so clearly and distilled its essence into the analogue dreamscape he created, but I’m forever grateful and can’t imagine this album without it.

Q: How collaborative was this process with Jordan? I can see that you’ve provided what appear to be images of your grandmothers. How aligned were you both on the film's vision?

MC: I gave Jordan some touchpoints, prompts and the locations to shoot, but the real work of shooting the film and understanding how it would all come together in the end was all his. I had complete faith in his vision and knew he would do something amazing, but the result still floored me. Watching it for the first time was very special.

Q: Monty, with all this thought put into ‘Water & Music’, it’s very likely that someone who watches or listens will have no idea of the context we’ve discussed here. With that in mind, is there one unifying feeling that you hope people take away from the record?

MC: Just a little bit of beauty, I’d say.

Q: If you could share this with your grandmothers, how do you think they’d feel?

MC: I’d like to think they’d be delightfully bemused. One day I’ll get around to pulling up at their graves and playing the album to them.

Q: Jordan, appreciate you taking the time to share. How has working with Monty on this release been?

JKK: From the birthing of this project, there was a mutual trust and connection. I could sense early on that what Monty had created was close to his heart, and that’s what mattered to me most. From there on, the floodgates opened, and we exchanged countless emails and phone calls about the inner workings of our worlds, our reasoning, our processes, and their intersection. Ultimately, this set up a very mutual respect for one another, which enabled the film work and my process to marinate and flourish over time with little to no pressure.

Q: As I understand it, when Monty asked you to be involved, you were away at an intensive filmmakers ‘jam’ weekend, playing with a brand new technique. Can you explain what that technique actually is, & how it works?

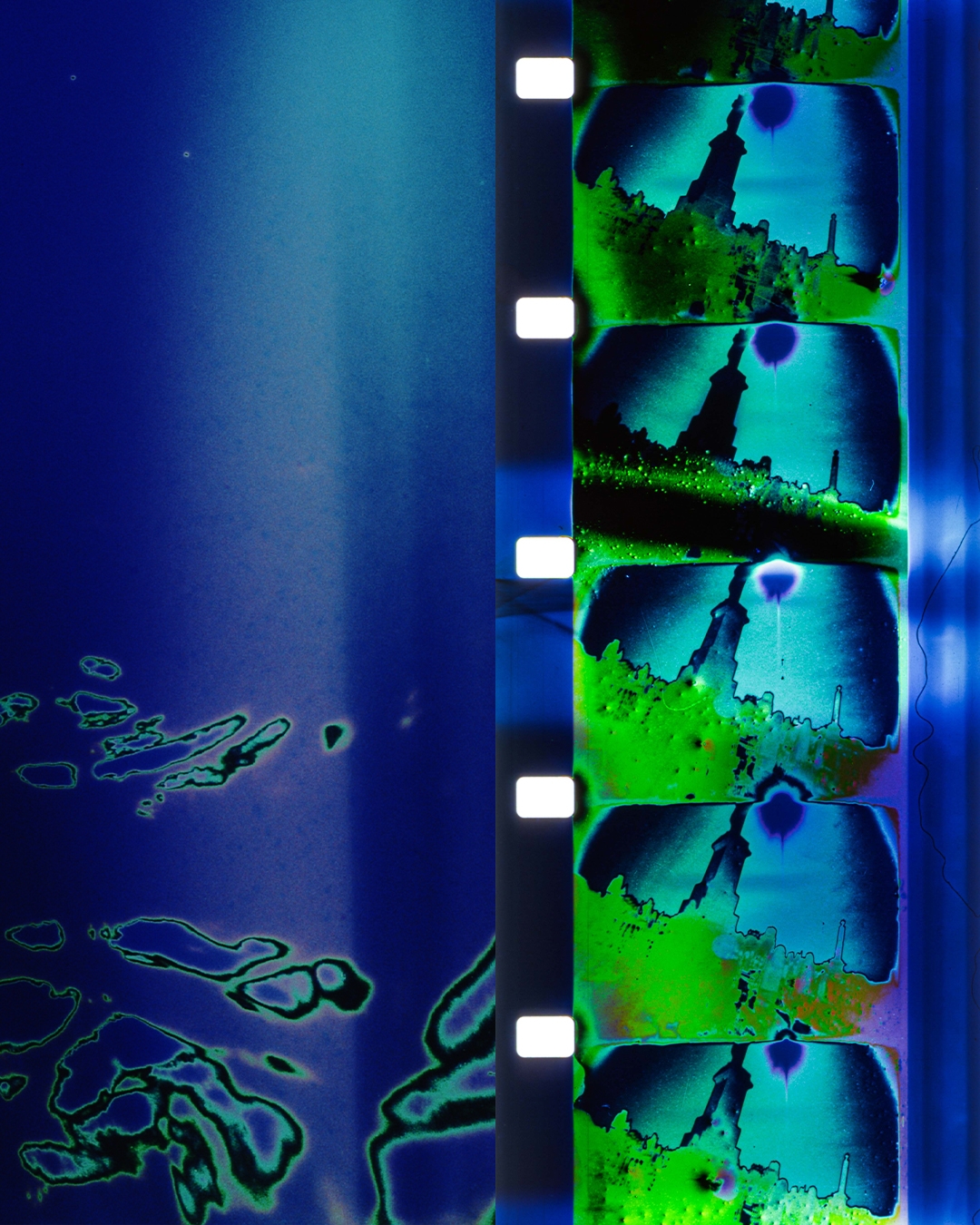

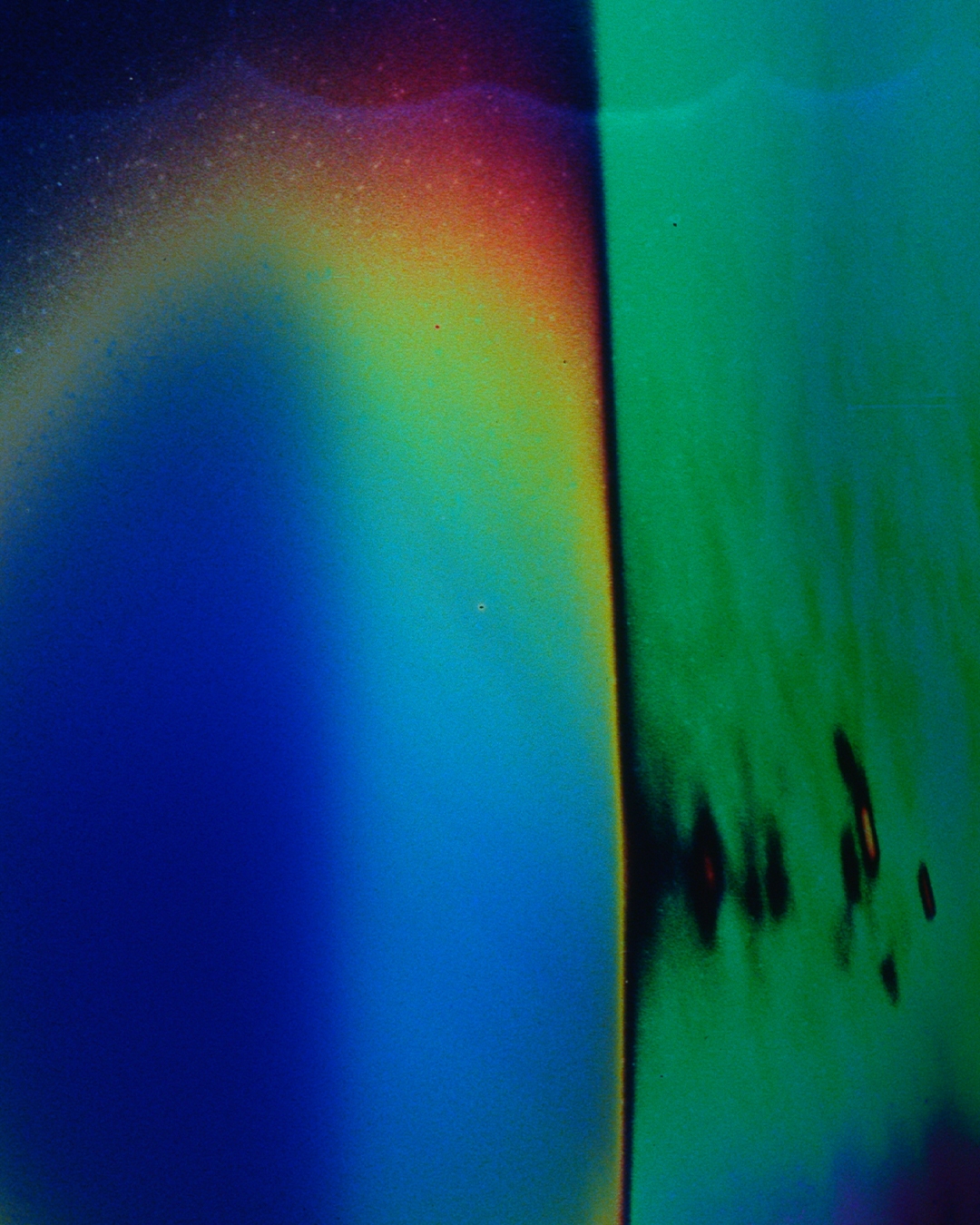

JKK: I was away at our annual Artist Film Workshop in-house/members, 20 of us or so, film festival called Nanofest run by the infamous Richard Tuohy and Dianna Barrie, who are the goated experimental filmmakers, imho. They were running a 16mm experimental workshop where we would be using this 16mm print film stock in a way that Kodak hadn’t intended anyone to use it. The film stock is ‘print film’ in that it is film used to strike a print, via usually a ‘contact printer’, from a camera negative film stock, producing a projector-ready print for projecting in an analog projector for cinema, etc.

SO, the interesting thing about it is it’s not made for use in a camera. Why? Many things. Because it demands so, so much light to produce an image. It inherently expects an orange mask from a camera negative. It is low-sensitivity, finely grained, with a limited, steep latitude, rated at 3ASA (give or take). The latitude information is limited, being that the highlights and the lowlights are the most pronounced parts of the image it makes up, meaning that the middle ‘grey’ area is somewhat lost, at least detail is lost there. Simply put, it’s great for shooting silhouettes with because you have a fall off and steep contrast between the highs and lows. It’s not made for shooting the real world; it’s made for making an image of the real world from stock you are meant to shoot the real world with. When you put this stock through a camera, you need to provide the film with as much light as possible, and when you chemically develop the results, you get a blue-cast image, naturally. The last and one of the most important things I’ll say about this film stock is that it is about 4 times as cheap as regular film stock, which is the reason we were able to produce a 45-minute film shot, developed, edited and printed entirely onto real 16mm film.

Q: Your first listen to ‘Water & Music’ was on the drive home from that weekend. What were you thinking when you felt Monty’s music aligning with the very work you’d just been doing?

JKK: Often in my creative process, there's a divine moment, an idea formulation spike and then a spark, and it’s usually massive, and it was. I had that spark on that drive back from that weekend. I knew I had Monty’s email sitting there, and I had been putting off listening to the album until there was that spark.

There I was thinking about this film stock, sitting at 100km/h in my brain and in my car, thinking about how transcendental the album is and what visual world the album deserves, thinking about how much light I need to shoot the thing, thinking about solarisation and Man Ray, thinking about which song I could make something for, thinking about the process it would take to just go ‘full monty’ and create an entire film and visual world for the music to find itself in heaven with.

The rest was history.

Q: Your use of 16mm film parallels Monty’s use of archival recordings in many ways. What does working with film do for you creatively, compared to, say, doing this project all digitally?

JKK: The archival recordings were a huge calling card for taking on this project. I appreciated Monty's respect for the analog material and his confidence in me to lead the charge on the analog and 16mm sides of the film. I just want to mention here that I made this film entirely by hand, with no digital intervention whatsoever (other than the final digital scan). This means that I developed the film chemically myself, I made a hand spliced edit of selected scenes from over 700metres of film material by quite literally cutting and taping the film segments together, and then striked an analog print using a Model C Bell & Howell contact printer which is our guardian angel at Artist Film Workshop (one of the only working machines of it’s kind in the country). The film is now an archival piece of history that will outlive anything digital.

I make all my own films on 16mm because it just feels like second nature, or maybe a version of home, it’s the realest way for me to take an idea and then to make it into something that feels real, tangible and physical, which it is. What working on 16mm film means for me is that I get to understand the material and the mechanics that wrestle with it to make it what it is.

For this film, specifically because of the film stock I was using and how much light it demanded of me and my camera, it brought me closer to the real world, as I had to consider what I had and then adjust the film stock through chemical development. Monty and I shot this film in a matter of days up in Mittagong over a pretty grey kind of weekend where we actually didn’t get much sun, and we needed it, we really hoped for it, too. Ultimately, the material is a being too, but I had a trick up my sleeve to give the film stock the light it demanded, so I interfered with the chemical development process by way of (pseudo) solarisation, a method developed by the infamous Man Ray.

What this meant was that even though there was limited light while we were shooting, through this solarisation process, I could alter the image midway through hand development and give it light at specific points, which creates this solarisation halo effect around the edges of distinguishable figures in the film itself. The film is a double solarised experiment, meaning that I solarised the film stock I ran through the camera, which I treated as the ‘negative’ and then solarised the master print ‘positive’ that I made through a contact printer.

What makes this film so special is that it is what’s called a single ‘mono print’, it’s a one-off, it can’t be exactly reproduced, there’s only one of them in the world, and it’s tucked away in a massive 2000ft tin in my film archive at home.

Q: This record is incredibly sentimental to Monty, being a culmination of many collaborators & influences, some of whom are no longer with us. What was it like to interpret that kind of emotion? How did you go about doing that?

JKK: I’m also blessed in that it is now incredibly sentimental to me, too.

I did this materially, and in a way by producing a film that, no matter the instance, the scene, the subject matter, there is always at play the matter of light in dark and dark in light, and neither is ever really distinguishable from one another.

What was at play throughout the film is seeing the world like you’re seeing all of the light and all of the dark simultaneously as equal parts. As in, all that is here in light is here, and for all that is gone is also here and in light, we see it in the film. I interpreted this thought and idea through the manipulation of the film by the method of (pseudo) solarisation. The way this technique builds into the emotional sensibility and sentimentality of the album is that it sheds light on the areas of the image where there is no information, no light, and via my method of double solarisation, I am affecting the image by ultimately flipping parts of the image in regards to it’s image ‘information’ multiple times.

Where it’s dark, it is light, and then where it is light is dark again.

What this achieves is an effect where it feels like you’re looking through the world in night vision goggles, subject matter carries the infamous solarised halo around in honour and our perception of what is light and what is shadow is skewed which brings on this ethereal and dream-like aesthetic which I wanted to be able to interpret especially the inclusion of Monty’s Grandmothers, who are no longer with us, and my understanding that what is gone can still live within us just as our shadows makes up an equal part of ourselves.

Q: What do you hope that a viewer takes away from the experience of listening to the album & watching its visualiser simultaneously?

JKK: Joy.

-

'Water & Music' is available for purchase digitally & as a limited edition CD via Climes' Bandcamp. Jordan James Kaye's accompanying film is available to view, in full, via Climes' Vimeo.

Climes will perform at Unfurl's 'The Blue Hour' at Lazy Thinking on Sat, Feb 28, alongside Sina, Khaled Kurbeh + Alexandra Spence, and Luke M de Zilva, Glen. Rey + Bildungsroman.