FEATURES

FEATURES

Colonial commentary on modern dance, via Yung Lemon's 'Don't Matter'

The release sees the Gadigal Land/Sydney producer working with a variety of creatives on an accompanying digital & physical zine, exploring the depths with which music is able to add comment.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, what is a visual or written story alongside music worth?

Increasingly, perhaps as a push away from the commercialisation of dance and electronic music, many musicians within Australia are pairing their work alongside those of other artists, writers and creatives. Whether as soundtracks to a story, an articulation of more complex ideas, or a juxtaposition with them, these musical projects are continuing to challenge the idea of what ‘form’ music needs to take upon its release.

‘Don’t Matter’ is described as an electronic club album, with five original tracks by Gadigal Land/Sydney-based producer Latif Rabhi, also known as Yung Lemon. However, the album is also paired with a chapter in an accompanying print zine of the same name, with every chapter corresponding to a track. Through a fusion of music, poetry, visual art and interview, the zine “explores metaphysical and sociopolitical dimensions of ‘nothingness’.”

Yung Lemon, whose musical work is anchored in his Algerian heritage and Amazigh rhythm, has worked with a series of collaborators to challenge this idea of ‘nothingness’ as it relates not only to music, but also to colonial constructs in Australia, Palestine, and Northern Africa.

At a time when these conversations have never been more intertwined within dance and electronic music, we secured a moment of Rabhi’s time.

Q: Latif, thanks so much for taking the time to speak with me. ‘Don’t Matter’ is a massive undertaking, and you’ve been working on it for four years. How did you decide that it was ‘done’?

YL: When I channel an idea rather than impose it, the feeling of something being ‘done’ is largely intuitive. This is why it took so long, because there was a lot of back and forth with the idea for it to form naturally. Between reflection, personal growth and collaboration, it’s kind of like star dust eventually forming into a star. It just happens, and you need to trust the process.

Q: What do you think the merging of the digital nature of electronic music with the physicality of a print zine meant for the project?

YL: I think music is always physical; otherwise, you won’t be able to hear it, whether it’s produced electronically or organically. The hypercommercial, consumable packaging of music can thin out that feeling. Having something tangible and tactile adds a personal touch. It comes from a real place. I want people to feel that.

Q: The zine is filled with five chapters, each corresponding to a different track from the release, all of which touch on the “metaphysical and sociopolitical dimensions of ‘nothingness’”. Why was this a topic you wanted to explore?

YL: The topic is my fascination. I love physics, science fiction novels and philosophy. The edge of science becomes philosophical. Magic is fundamental to science because, without imagination, we wouldn’t be able to create hypotheses to test in the first place.

There is a kind of empty space outside of what is known that feeds into our reality. I find the richness of that super fascinating. I am also inspired by the art style of erasure - obscuring elements of an existing work to create new levels of meaning. Erasure is all around us, especially in colonial cultures such as Australia. The work aims to inspire people to look into this and reflect on it.

Q: You’ve worked with a series of artists on the zine. How did they come to be involved?

YL: These artists are my community. They inspire me, and my work is a reflection of theirs. I don’t think we create in a vacuum. I wanted to include them because I love their art and trust their ability to represent the concept. Building as a community rather than as individuals helps ideas thrive.

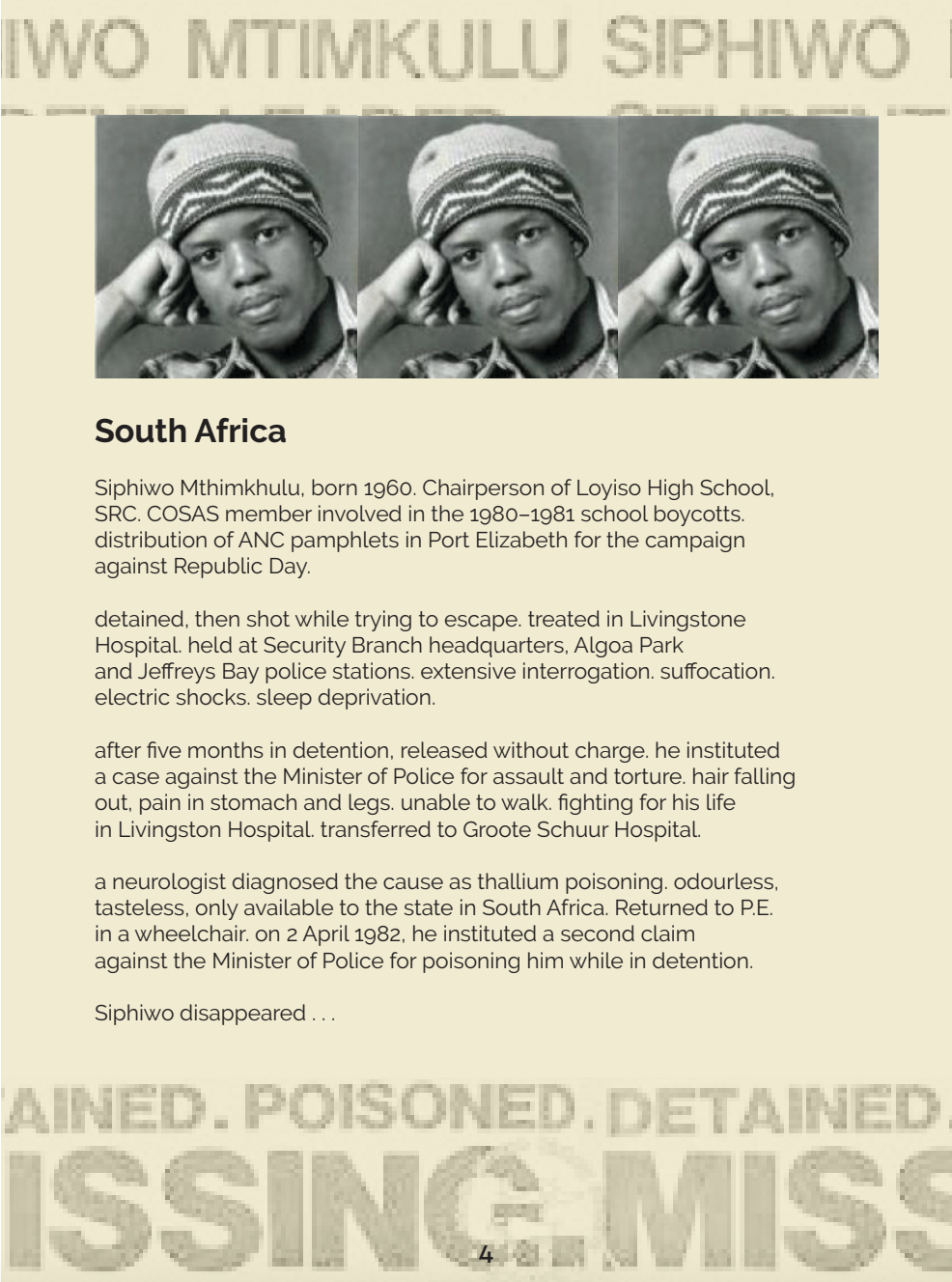

Q: Within the zine, there is a story of Siphiwo Mthimkhulu, a South African man who was tortured by South African police, made complaints against them, and in 1982 disappeared. How did you become familiar with Siphiwo’s story & why was this important to include in this zine?

YL: The Colonial Culture chapter was written by Gaele Sobott, who lived in Southern Africa for many years and experienced life under Apartheid. She called the work, “Extracted: the colonial war continuum”. It consists of three extracts or found poems from the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report, Queensland coroner reports and the Palestine Museum.

This section deals with the historic and continuing violence of colonisation. It links to the zine themes on many levels. One is where the lives, culture, histories and futures of colonised people ‘Don’t Matter’, another is the concept of terra nullis. The violent land theft and occupation is justified by claiming there was nothing there before the colonisers invaded and occupied the land. These arguments are still used to justify the ongoing extremes of violence.

Q: At a number of points, the zine discusses and highlights the struggles of Palestinian people, including an interview with a Palestinian dentist by the name of Dina Turkeya. How do you feel that this interview should be read in conjunction with the track ‘Speak No Evil'?

YL: Dominant media, and the government of many countries, including Australia, have covered their mouths, their ears, and their eyes to the horrific genocide in Gaza and the ethnic cleansing of the West Bank.

They refuse to speak of this evil.

They refuse to act to stop it but are collaborating with the extreme brutality and profiting from it. The Palestinian writers and journalists who tell the story of the horror are assassinated. They are a source of truth. They speak no evil.

Q: What do you think the accompanying track ‘Colonial Culture’ means in a modern context?

YL: Colonial culture uses the Algerian Rai beat, which is a genre of resistance. The Algerian story is an integral case in pathways to resisting empire. If you come from a colonised people, you are sensitive to the insidious ways colonial culture operates.

I love cosmic horror novels, and I see parallels between cosmic horror monsters and colonial culture. It’s a multidimensional beast, which poisons the earth, society, and culture.

Q: There’s a continuing conversation that ‘politics has no place on the dancefloor’. This release takes that sentiment & pushes it entirely the other way, with each track dripping in political context. Do you think that ‘dance’ music can be a proper vessel for political discourse?

YL: Raves have always been a place of resistance and politics. If something is non-political, it’s just supporting the dominant political narrative. I think people say that to evade responsibility. Dance music has historically been a vessel for political discourse and resistance, whether it’s Techno, Baile Funk or Rai.

Q: Since October 7 in particular, we’ve seen compilations, tracks and releases sharing profits with Palestinian people and organisations. What do you think these kinds of actions could do to improve their commitment to the Palestinian people truly?

YL: In terms of donating, I think it’s best to donate to Palestinian mutual aid groups who are on the ground in Gaza. Organisations like Water Is Life Gaza.

We also need to use our creative platforms to pressurise the Australian government into taking real actions, sanctioning Israel, and immediately stopping the two-way arms trade. It is beyond urgent.

Q: How do you think that your Algerian heritage has influenced the way that you’ve gone about creating this work, and how has it influenced where you see yourself in Australia’s dance music ecosystem?

YL: I love our culture, language and music and want to share that with the world. Rave and trance-inducing music is deeply Algerian. If you trace our dance music ecosystem further back than Chicago, you will arrive in North and West Africa. I envision myself as a pioneer in helping dance music return to its roots by blending traditional elements with modern bass and sound system compatibility.

Q: If a picture can tell a thousand words, what do you think these artworks alongside your music can do?

YL: I think the visuals add unique layers. I love the work that VDJs and set designers do at events. I think that part is super important and helps to provide a full picture and story behind the sound.

Q: What kind of impression do you want this project to leave upon listeners & readers?

YL: I would love for the project to leave people feeling curious and inspired. Hopefully, listeners and readers will see the depth and power in nothingness and its relationship with colonial structure and power.

-

‘Don’t Matter’ is available as a digital download & a limited edition zine via Yung Lemon’s Bandcamp.

-

Jack Colquhoun is Mixmag ANZ’s Managing Editor, find him on Instagram.